Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 12

Introductory Remarks

The macroprudential diagnostic process consists of assessing any macroeconomic and financial relations and developments that might result in the disruption of financial stability. In the process, individual signals indicating an increased level of risk are detected based on calibrations using statistical methods, regulatory standards or expert estimates. They are then synthesised in a risk map indicating the level and dynamics of vulnerability, thus facilitating the identification of systemic risk, which includes the definition of its nature (structural or cyclical), location (segment of the system in which it is developing) and source (for instance, identifying whether the risk reflects disruptions on the demand or on the supply side). With regard to such diagnostics, the instruments are optimised and the intensity of measures is calibrated in order to address the risks as efficiently as possible, reduce regulatory risk, including that of inaction bias, and minimise potential negative spillovers to other sectors as well as unexpected cross-border effects. What is more, market participants are thus informed of identified vulnerabilities and risks that might materialise and jeopardise financial stability.

1. Identification of systemic risks

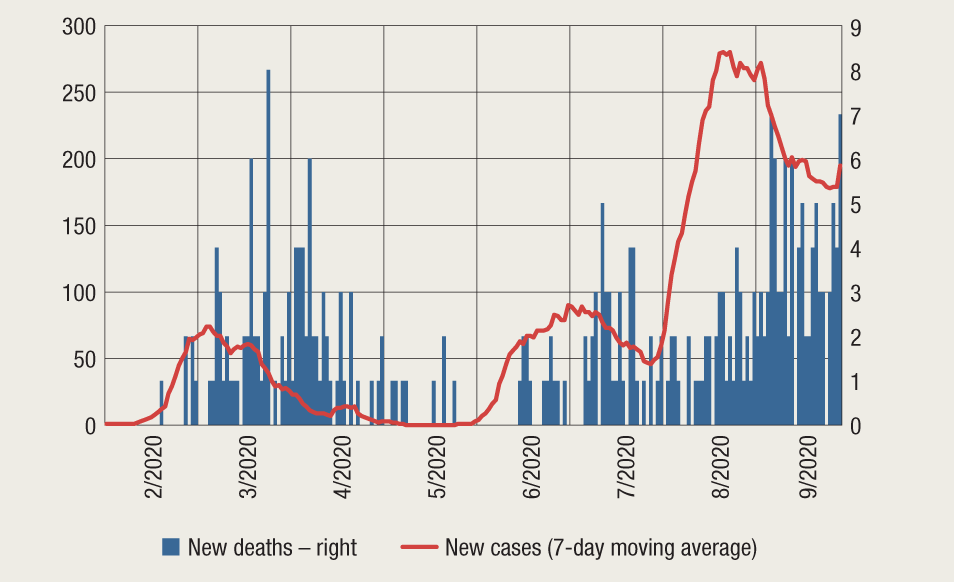

Over the previous half of the year following the proclamation of the COVID-19 global pandemic the number of new cases rose steadily throughout the world. Since the end of summer, European countries have witnessed “a new wave” of the epidemic, with a record surge of new cases. Nevertheless, the epidemiological measures in European countries continue to be less restrictive than during the first wave, which can be attributed to the progress achieved in the implementation of target measures to control virus transmission and to the reduced fatality in the past several months. No significant strengthening of the intensity of epidemiological measures that would restrict movement and economic activity in Croatia is likely. This reduces the risk of new strong shocks that would increase systemic risks in Croatia and pose a threat to financial stability. However, the uncertainty regarding future course of the pandemic and the threat that the virus will pose to human health during the autumn and winter months remains extremely high, particularly if account is taken of the fact that no medical solution in the form of a vaccine or efficacious treatment will be available this year.

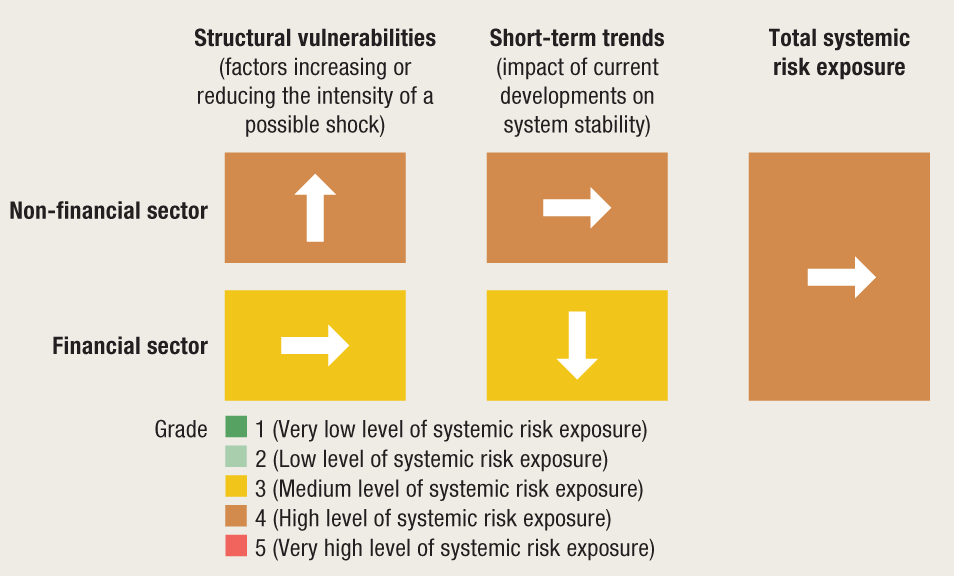

Figure 1 Risk map, third quarter of 2020

Note: The arrows indicate changes from the Risk map in the second quarter of 2020 published in Financial Stability No. 21 (July 2020).

Source: CNB.

Despite indications of stabilisation and more favourable expectations regarding future economic developments in relation to mid-year expectations, the overall exposure to systemic risks at the end of the third quarter remained high (Figure 1). As compared to the Risk map published previously in Financial Stability No. 21, short-term risks fell slightly while structural risks rose. More specifically, due to a series of implemented measures to mitigate the consequences of the pandemic on the economy, it is possible that some risks will materialise with a delay.

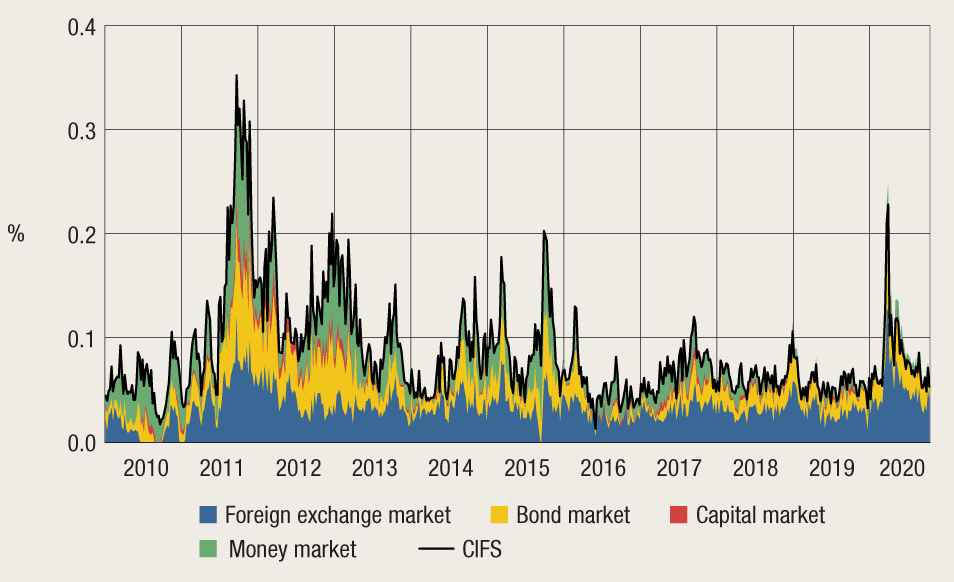

Financial markets calmed down after the short-term turmoil in March (Figure 2). The CNB took a number of coordinated monetary policy measures in spring. In particular, interventions in the foreign exchange market and direct purchase of government bonds from a wider range of financial institutions, stabilised the exchange rate and alleviated disturbances in the government bond market, easing uncertainty in the domestic financial market and maintaining favourable financial conditions. The stabilisation of the conditions in different segments of the financial market is seen in the index of financial stress, which fell to the usual pre-crisis level. The CNB will continue to pursue a monetary policy based on exchange rate stability. This is gaining in importance in the light of participation in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II), which Croatia joined on 10 July this year with the central rate of the kuna being set at 1 euro = 7.5345.

Figure 2 Developments in the financial stress index for Croatia

Note: Data shown are data available as at 2 October 2020.

Sources: Bloomberg and CNB calculations.

Recent monthly indicators of economic activity in Croatia suggest a gradual recovery, however, with lingering uncertainty regarding developments in the coronavirus pandemic. Following a sharp fall in economic activity in the second quarter, the economy has been showing signs of recovery in the past few months. Towards the end of the second and early in the third quarter recovery was seen in industrial production and construction in contrast with the biggest fall that was seen in service activities requiring greater social contact, the activities hardest hit by social distancing measures. Despite expectations that tourist turnover in 2020 in Croatia could fall by approximately 70% or even by 90% under a most pessimistic scenario, due to the coronavirus pandemic, the number of arrivals and overnight stays by foreign tourists in the July to August period was much more favourable. According to data provided by the “e-Visitor” system, in the first eight months of the year, the number of nights stayed by foreign tourists fell by 48% from the same period of the previous year. However, the financial impact of the export of tourist services will be negatively affected by lower prices of package holidays and changes in the structure of tourist consumption, which is also associated with a sharper fall in tourist arrivals from countries with a relatively high average consumption. In addition, the worsening of the epidemiological situation in Croatia towards the end of August and the introduction of preventive measures in emitting markets for persons returning from Croatia will have a negative impact on tourism in the rest of the year. Taking into account the more favourable economic developments in the past few months, the fall in gross domestic product in 2020 might be smaller than that predicted by the CNB in May this year (Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 11). However, the fall in real GDP in 2020 might be sharper than that after the outbreak of the GFC in 2008.

Consumer and business expectations in all activities were more favourable than in spring but are still well below pre-pandemic levels. The rise in consumer optimism was driven by an improvement in the expectations regarding overall economic activity and the financial situation in households in the next 12 months. However, expectations regarding the purchase of durable goods over the next year deteriorated, suggesting that demand remains subdued. Also, continued pronounced uncertainty regarding developments in the pandemic and future demand is having a negative impact on new investment and employment in non-financial corporations.

The level of public debt rose sharply, presenting a pronounced structural risk over a medium term. Lower budget revenues and an increase on the expenditure side due to the measures to alleviate the negative economic effects of the pandemic fuelled public debt strongly. The financial position of the state was significantly facilitated by the use of EU funds,, in particular the possibility of the use of the unused funds earmarked for financing the expenditures caused by the pandemic (e.g. for health care, support for employment preservation). The government met the increased financing needs mostly on the domestic market and to a lesser extent abroad. After yields on government bonds rose at the onset of the pandemic, to alleviate the initial negative impact of the crisis, the CNB intervened in the bond market through a bond purchase programme, thus increasing liquidity on that market. The market calmed down after the bond purchase and the spread between the domestic yield and the benchmark non-risky bonds fell to the pre-crisis level. In addition, in the second half of September, Standard&Poor's confirmed that Croatia had maintained the investment grade rating (BBB–/A-3), with stable outlook. However, it should be noted that the increased level of public debt, along with pronounced risks of additional growth in the case of a growing pandemic and economic contraction during the winter, is one of the most pronounced macroeconomic imbalances. High sovereign exposure risk has a big impact on financial stability because of the considerable financing by the domestic banking system and other financial intermediaries.

The risks in the non-financial private sector are elevated at the moment, while vulnerabilities depend on the dynamics of economic recovery and the efficiency of the measures aimed at alleviating the economic impacts of the crisis. Good business results in 2019 made it possible for a large number of companies, especially small companies, to build shock buffers in the form of accumulated liquid funds and capital, which will be used partly to bridge liquidity gaps. Despite falling indebtedness of the corporate sector over the previous years, this sector still had a relatively high level of debt at the time of the outbreak of the crisis, which even rose further, slightly fuelled by demand for liquid assets following the outbreak of the pandemic. However, after a considerable growth in working capital loans granted in March and April, these loans started trending downwards, while there were almost no new investment loans. This was the result of credit standards tightening for all types of loans but also large uncertainty, which had an unfavourable effect on demand, which fell for all loans except those for existing debts restructuring. Given the different intensity with which the initial impact of the crisis has affected companies (see: Financial Stability No. 21, chapter Non-financial corporate sector), the speed and intensity of the recovery of operating income will differ greatly from activity to activity. Data on fiscalised accounts also suggest big differences among activities. The value of these accounts fell the most in the activities of hotels and restaurants and transport.

Insolvency risk is most pronounced in the segment of small and medium-sized enterprises. Small and medium-sized enterprises are predominant in the currently vulnerable activities (hotel accommodation, restaurants, transport, and entertainment industry). These enterprises are more sensitive to diminished volumes of operations and increased risk premiums and generally have a more difficult access to favourable funding and almost no access to external sources of funding. However, the risk of (in)solvency of these enterprises is offset by their good business results in the previous year, which fuelled considerable growth in deposits, particularly in the case of small and micro enterprises, which facilitated liquidity shock absorption at the onset of the crisis. Capital grew sharply in 2019; by 14% and 25% in small and large enterprises, respectively.

The uncertainty regarding future trends in the labour market and developments in personal income increase household sector vulnerability. Ample government measures in the second quarter aimed at supporting job preservation, later limited to especially hit companies, mitigated unemployment growth. However, vulnerabilities remain elevated due to great uncertainty regarding future trends in the labour market and developments in income. Coupled with lower consumer optimism, this slashed household demand for general-purpose cash loans, while the growth in housing loans accelerated in the second quarter driven by the government programme of housing loan subsidy and the reconstruction of buildings damaged in the earthquake. The ability of households to continue servicing their financial obligations amid lower income is important for macroeconomic and financial stability because of banks' level of exposure to that sector, which accounts for almost one third of their total assets.

Possible reinstitution of foreclosure in relation to citizens' financial obligations and expiry of the moratorium on debt repayment are fuelling further uncertainty in the household sector. The financial position of households has improved in the previous months owing to the agreed moratorium on credit obligations (3 to 12 months) and temporary suspension of foreclosures in April, extended in July from the initial three months to six months (Decision on the extension of the duration of special circumstances (OG 83/2020)). The decision on the suspension of foreclosures expires in mid-October and the agreed moratoria expire now or in early 2021, depending on the initially agreed time limit.

The residential real estate market has recorded a fall in activity, while prices continue to grow, driven by the government's subsidy programme taking place in spring and autumn 2020. In the first half of 2020, the number of transactions on the real estate market fell considerably from the same period of the year before, and the average prices of residential real estate, measured by the hedonistic index calculated based on purchase and sale transactions continued to rise, reaching record highs. The bulk of purchase and sale activities in the second quarter was associated with the implementation of the Government’s programme of subsidising APN loans. Over the four years of programme implementation, 13 thousand subsidised loans were granted, of which 3 618 were granted under the spring 2020 programme. If the programme's further implementation in October is taken into account, it is evident that the programme is growing steadily, which coincides with acceleration in housing loans growth. Although the earthquake that hit Zagreb and its surroundings led to a significant decrease in the value of the housing stock, it is not expected to have a direct impact on price developments measured by the hedonistic index due to its construction (the difference in the quality of housing units is taken into account). However, due to a fall in the number of usable housing units, i.e. reduction in housing supply, it is possible that the earthquake added to the growth in the prices of housing units in and around Zagreb.

Poorer overall liquidity of the real estate market might increase the risks to financial stability. However, the negative impacts of low market liquidity on banks' balance sheets, associated with collateralised exposures, are mitigated by a currently high coverage of non-performing exposures. In addition, further implementation of the housing loan subsidy programme might continue to fuel real estate prices in the future, while mitigating the negative impact of unfavourable macroeconomic developments. Taking into account the lower level of employment relative to the beginning of the year, higher price level diminishes residential real estate affordability.

High banking system liquidity and capital level facilitate post-crisis challenges. Influenced by the CNB's expansionary monetary policy, the daily surplus of free kuna reserves of the domestic banking system reached record high, exceeding HRK 40bn at the end of August. The liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) reached almost 200% towards the end of August and none of the banks had to turn to supervisory relief measures aimed at alleviating the impacts of the pandemic, which enables them to keep this indicator even below the regulatory minimum of 100%. High system capitalisation was also preserved by supervisory actions in relation to the banks, with the CNB ordered the banks in March 2020 to retain the profit generated in the previous year.

Further support to additional stability and the resilience of banks to the impacts of the pandemic was provided by not only CNB supervisory action but also by EU-wide regulatory changes introduced by Regulation (EU) 2020/873 amending Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 (CRR) as regards certain adjustments in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (the so-called CRR ”quick fix”). The most important result of these changes for domestic banks is easier placement of loans to the government in foreign currency, the euro. Namely, the reinstituted application of the 0% preferential risk weight for exposures to central governments and central banks in currencies of other member states (which already at the end of June 2020 led to a fall in the risk-weighted assets of banks) and increased the exposure limit[1]. Other changes involve adjustments of the time limits for the implementation of IFRS 9 on the capital of credit institutions, more lenient treatment in the case of public guarantees given during the crisis in relation to non-performing exposures, postponement of the date of application of the leverage ratio buffer, the change in the manner in which certain exposures to central banks are excluded from the calculation of the leverage ratio, etc.

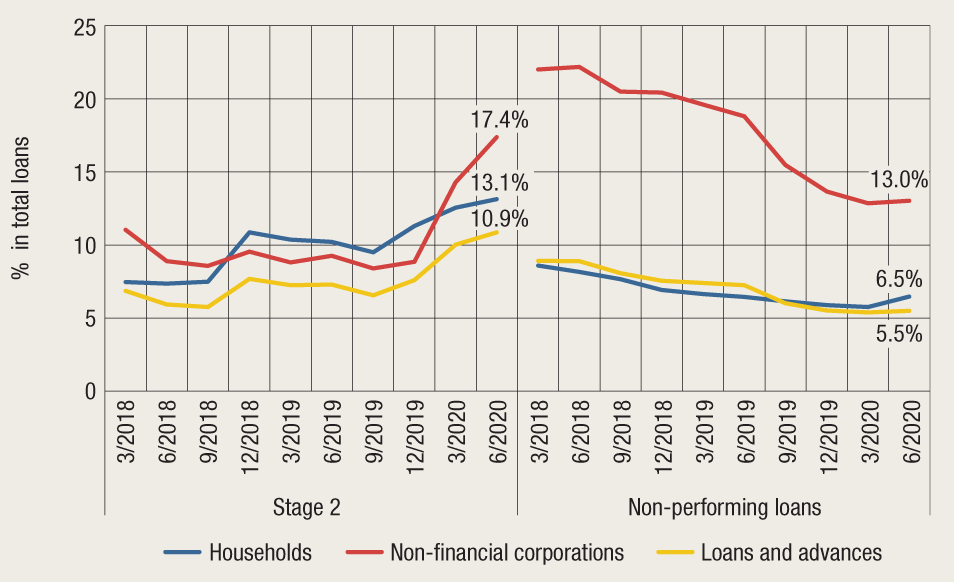

The current impact of the coronavirus pandemic on credit institutions is mirrored in a considerable increase in credit risk in performing exposures, while no significant growth in non-performing loans has been recorded yet. Since March, the banks have continuously recognised a significant increase in credit risk in the system, which resulted in a sharp rise in assets classified in Stage 2 - increased credit risk since initial recognition (Figure 3) and which is subject to impairment. The biggest increase in these exposures relates to loans to non-financial corporations, the share of which doubled until the end of June from the end of 2019. Loans to households in Stage 2 recorded a somewhat smaller increase and in the past few months their share in total loans stagnated.

Figure 3 Share of loans in Stage 2 (performing loans with a recognised increase in credit risk) and share of non-performing loans in total loans

Source: CNB.

Owing to the adjustment of the rules on classification relating to granted moratoria, the share of non-performing loans in total loans held steady. The amount of non-performing loans rose only slightly in the first half of the year influenced by the adjustment of supervisory expectations regarding exposure classification for granted moratoria. Additionally, credit activity exceeded the nominal growth in non-performing loans, so their share remained steady at 5.5% (Figure 3). The growth in loans was mostly associated with affiliated financial institutions abroad through short-term repo loans and with the central government. In the segment of private sector lending, of household loans, housing loans rose, while credit activity involving corporations and other forms of household lending slowed down. Considerable deterioration in credit quality was observed in the household sector, which witnessed an increase in non-performing loans in all major instruments, although portfolio worsening can mostly be attributed to unsecured general-purpose cash loans. Unlike households, non-financial corporations saw only a small increase in non-performing loans, which may be explained by a greater number of moratoria granted in this sector (see: Analytical annex Preliminary information on fiscal measures and moratoria introduced to mitigate the impact of the pandemic). The coverage of non-performing loans by impairments continues to be high at 67.8%, so that they currently exert no additional pressure on bank capital.

Bank profitability fell considerably in 2020 as a result of a fall in interest income and higher impairment costs but so far it seems that the banks will be able to cover impairment costs from operating profit. At the end of the first half of 2020, banks reported almost half a lower profit than in the same period of the previous year. As a result, profitability indicators halved, with ROAA standing at 0.9% and ROAE at 5.6%. With a fall in all the components of operating income amid declining economic activities, a negative contribution to profitability also arises from the mentioned increase in provisions under new non-performing loans and performing loans with a significant increase in credit risk (Stage 2). Additional pressure on bank profitability is also created by low interest rates on the global financial markets, which led to a further fall in bank lending and deposit rates in Croatia. The expectation is that over-indebtedness, insolvency of some of the corporations and households once the moratorium expires will lead to asset deterioration on banks' balance sheets, and that the banks will shoulder part of the losses.

High banking sector exposure to the central government, which increased additionally following the outbreak of the crisis, is a considerable source of risks. Strong fiscal consolidation at the beginning of the crisis, mainly financed on the domestic market, further increased the already present risk of high banking system exposure to the central government through granted loans and investments in securities. Also, unlike the previous crisis when government yields were much higher, the current increase in the share of this sector in banks portfolios poses a challenge for bank profitability, already marred by low interest rates.

2. Potential triggers for risk materialisation

Any stronger worsening of the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic during the winter might put off economic recovery in Croatia and the rest of the world. With winter approaching, respiratory diseases are expected as well as a possible surge in the number of persons infected by the coronavirus and in fatalities. Should the health care system capacity start reaching its limits, any decision on restrictive epidemiological measures and stronger measures of voluntary social distancing would have a negative impact on confidence. This course of events would impede regular operations and additionally slow down or postpone economic recovery. Job losses and renewed pressure on the labour market and corporate and financial sector balance sheets would additionally impede the expected recovery trajectory.

Figure 4 Croatia: New cases and deaths caused by COVID-19

Source: Koronavirus.hr, data as at 2 October 2020, processed by the CNB.

Slower economic recovery and growing private sector debt might aggravate repayment ability over the next medium term and pose a solvency risk. Increased corporate borrowing early on in the crisis helped them overcome liquidity pressures and, coupled with economic policy measures introduced at the beginning of the pandemic, mitigated the initial shock on corporate balance sheets (especially in the services sector and in corporations with insufficient liquidity or high debt). Credit quality of the corporate sector on banks' balance sheets is already showing signs of deterioration, and developments in this sector could be one of the main sources of instability for the domestic banking sector. On the other hand, over recent years, households have also accumulated debt associated with unsecured cash loans, some of which are already showing significant signs of being in default.

In the international environment, a big emphasis is placed on economic policy makers; any wrong steps in responding to the pandemic, such as premature relaxation of the support measures might lead to turmoil in the financial markets and the tightening of financial conditions. Risks in the international environment until the end of the year are also associated with the completion of the Brexit process and growing political tension in connection with American presidential elections in November, which might postpone the new fiscal stimulus to the US economy.

3. Recent macroprudential activities

3.1. Continued application of the countercyclical capital buffer for the Republic of Croatia in the fourth quarter of 2021

Due to the need to ensure continuity of bank lending to the non-financial private sector amid the worsening of economic developments as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, the countercyclical capital buffer that will be applied in the fourth quarter of 2021 will remain 0%. As the competent macroprudential body, the Croatian National Bank will continue to regularly monitor economic and financial developments and will in this capacity act in coordination with monetary policy measures and supervisory measures, all with the aim of accelerating and facilitating economic recovery following the crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

3.2. The establishment of close cooperation between the European Central Bank and the Croatian National Bank and entry into the European exchange rate mechanism

After successful implementation by the Republic of Croatia of the measures undertaken under the letter of intent of July 2019, in July 2020, the Croatian kuna entered the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II). At the same time, the Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB) adopted a decision on the establishment of close cooperation with the Croatian National Bank and thus since 1 October 2020, the ECB has been responsible for the direct supervision of credit institutions assessed as significant in the Republic of Croatia and for common procedures relating to all supervised entities. The establishment of close cooperation will enable the Republic of Croatia to participate in the Banking Union where decisions are made on the supervision on the consolidated level of groups of credit institutions operating in the EU, which contributes to safety and stability of the banking system in the RC. In addition, in the area of macroprudential policy implementation, following the establishment of close cooperation, the Croatian National Bank will cooperate with the ECB that will have the authority to tighten national macroprudential measures if it assesses that they are too relaxed. Furthermore, from the date of entry into force of the decision of the ECB on close cooperation, the Republic of Croatia will also participate in the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM).

3.3. Recommendations of the European Systemic Risk Board

In response to the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic and the impact that it could have on the financial stability of the European Union, in June 2020 the European Systemic Risk Board issued several recommendations aimed at mitigating the risks to financial stability and increasing financial institutions' resilience amid the pandemic.

3.3.1. Recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board on restriction of distributions during the COVID-19 pandemic (ESRB/2020/7)

Further to the March 2020 recommendation of the European Central Bank that at least until 1 October 2020 no dividends should be paid out and no share buy-backs be made for 2019 and 2020, and similar actions by other national supervisory authorities in the countries of the EEA, the European Systemic Risk Board issued Recommendation (ESRB/2020/7) under which at least until 1 January 2021 relevant authorities request financial institutions under their supervisory remit to refrain from undertaking a dividend distribution or giving an irrevocable commitment to making a dividend distribution, from buying-back ordinary shares or creating an obligation to pay variable remuneration to a material risk taker, which has the effect of reducing the quantity or quality of own funds at the EU group level (or at the individual level where the financial institution is not part of an EU group), and, where appropriate, at the sub-consolidated or individual level.

Similarly, the CNB instructed the banks individually in mid-March 2020 to withhold last year's net profit and adjust the payment of variable remuneration. The so-called COVID-19 Circular was issued together with relaxed regulations on liquidity maintenance and classification of non-performing placements and aimed at mitigating the direct negative impact of the pandemic on liquidity and bank capital.

3.3.2. Recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board on monitoring the financial stability implications of debt moratoria, and public guarantee schemes and other measures of a fiscal nature taken to protect the real economy in response to the COVID-19 pandemic

As one of the measures to prevent the negative impacts of the pandemic on the economy, member states have introduced moratoria on debt, government guarantee schemes and other measures of a fiscal nature to protect non-financial corporations and households. Since the various measures implemented by one member state will have an impact on other member states through positive or negative spillovers, the ESRB will monitor and take into account the effect of such national measures on the financial stability of the European Union, and will pay special attention to their cross-border and cross-sectoral implications. To be able to do that, the ESRB has requested national macroprudential authorities to report on implemented national measures (see: Analytical annex).

3.4. Implementation of macroprudential policy in other countries of the European Economic Area

After many relaxations of macroprudential instruments that followed the outbreak of the pandemic, some member states decided to further relax measures in force in the third quarter. The Czech central bank thus again reduced the countercyclical capital buffer, from 1.0% to 0.5% from 1 July 2020 and relaxed the recommendation related to the assessment of new mortgages by cancelling the use of the maximum permitted debt-service-to-income ratio (DSTI). The countercyclical capital buffer was further reduced from 1 August in Slovakia too, from 1.5% to 1.0%. The Greek central bank took the decision to postpone for a year the phase-in of the buffer for other systemically important institutions. The central bank of Malta relaxed measures aimed at users of loans secured by residential real estate.

In addition to the actions taken to mitigate the effects of the pandemic, some countries continued to implement and introduce measures to curb systemic risk growth. With the July 2020 decision, France extended the implementation of the measure under which the large exposures referred to in Article 395, paragraph (1) of Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 to highly indebted large non-financial corporations with a head office in France are limited to 5% of eligible capital. Latvia saw the entry into force of a number of macroprudential measures aimed at consumers introduced towards the end of 2019. More specifically, in addition to the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, since June 2020 debt-service-to-income (DSTI) ratio and debt-to-income (DTI) ratio have been introduced, and maturity on housing and consumer loans has been limited.

These activities are also in line with the Recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB/2020/8) on monitoring the financial stability implications of debt moratoria, and public guarantee schemes and other measures of a fiscal nature taken to protect the real economy in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This recommendation aims to encourage exchange of experience among EU member states regarding the use of various measures and early identification of cross-border and cross-sectoral issues and these data are planned to be used later also for a coordinated approach to the gradual cancellation of individual measures. ESRB information on measures by countries are publicly available and will be regularly updated and some selected measures are shown in the Overview of selected measures from the ESRB database and supranational mechanisms of economic assistance shown below.

ANALYTICAL ANNEX

Preliminary information on fiscal measures and moratoria introduced to mitigate the impact of the pandemic

In the period that followed the escalation of the coronavirus pandemic, economic policy makers took a number of unprecedented measures with the aim of easing the panic on the financial markets, stabilising and facilitating operating conditions made difficult by the introduced epidemiological measures. In addition to the activities of central banks and other financial market regulators, fiscal policy measures played a particularly important role in mitigating the impacts of the pandemic due to their scope and range.

Even though the measures taken in the form of government subsidies and guarantees and other fiscal measures focus primarily on non-financial corporations and households, they undoubtedly have or will have an impact on financial stability. In this context in Croatia particularly noteworthy are direct payments of compensations for salaries of employees in companies witnessing a large fall in income and various forms of deferral of tax and social contributions or full exemptions from the payment of parts of these obligations for certain groups of persons that are subject to them. The position of debtors was also positively influenced by the moratorium on their obligations introduced by the banks, non-banking financial institutions and HBOR and HAMAG-BICRO.

To evaluate the intensity and efficacy of these measures in mitigating the impacts of the pandemic and their effect on financial stability and assess the possibility of relaxation and/or abolishment of the existing measures or the introduction of new measures, the CNB has started collecting relevant data from institutions implementing them – the Ministry of Finance, Tax Administration, HBOR, HAMAG-BICRO and the banks, and in cooperation with HANFA and non-banking financial institutions, the central bank has started collecting data on the amounts granted under individual measures and the number of applications submitted and granted.

Since there are many institutions actively participating in the implementation of the measures, the process of data collection is very complex and data at this stage are preliminary and may be incomplete in some segments, because some of the applications for certain measures are still being processed. Nevertheless, data shown in this overview of the measures taken in Croatia are a good starting point for the examination of the range of measures and their potential implications on public finances, the household and non-financial corporations sectors and the financial sector, and by extension on systemic risks and financial stability. In this context particular note should be taken of potential risks that are currently hidden due to the measures taken but could materialise once these measures are cancelled.

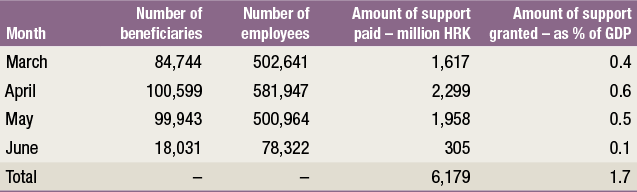

In Croatia, the employee support that the government granted through the Croatian Employment Service to companies that recorded a fall in income of at least 20% had a big impact on budget expenditure growth. In March, April, May and June over 72 thousand applications by companies were granted for this type of support, totalling approximately HRK 6.2bn.

Table 1 Employee support, 30 June 2020

Note: Shown as a share of the estimated GDP in 2020 (CNB projection).

Sources: Croatian Employment Service and CNB calculations.

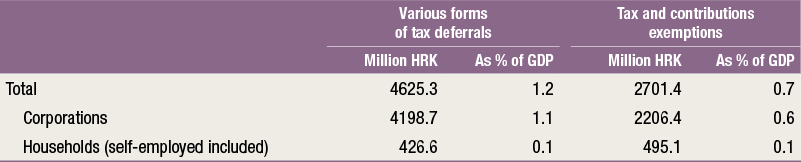

In addition, to facilitate further the real sector's adjustment to the new circumstances, until end-June, the government postponed the collection of HRK 4.6bn in tax and social contributions and wrote off HRK 2.7bn worth of tax and social contributions.

Table 2 Tax and social contributions deferrals and exemptions, 30 June 2020

Note: Shown as a share of the estimated GDP in 2020 (CNB projection).

Source: Tax Administration.

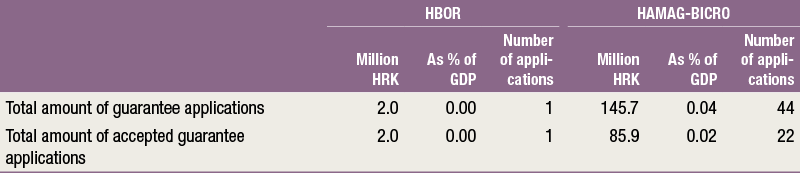

To ensure corporate liquidity the government also secured guarantees to exporters' banks and HBOR in the framework of the guarantee fund ensuring exports with the aim of granting new loans for working capital. However, the attempts to invigorate corporate credit activity have not been very successful as suggested by data until end-June since only one company applied for a HBOR guarantee, which was granted in the amount of HRK 2.0m. HAMAG-BICRO achieved somewhat better results, having secured guarantees and favourable loans for small and medium-sized entrepreneurs, and of 44 received applications for guarantees, a half were granted, totalling HRK 85.9m.

Table 3 Government guarantees granted through HBOR and HAMAG-BICRO, 30 June 2020

Note: Shown as a share of the estimated GDP in 2020 (CNB projection).

Sources: HBOR and HAMAG-BICRO.

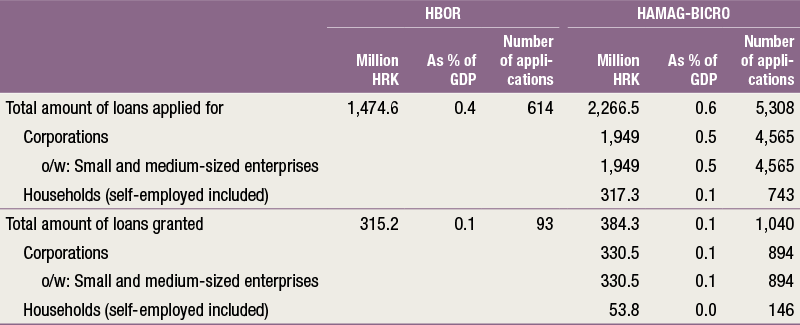

At the same time, of 614 loan applications through HBOR, only 93 were granted, totalling HRK 315m, while HAMAG-BICRO granted a little over one thousand loans, or only one-fifth of the received applications, totalling HRK 384m.

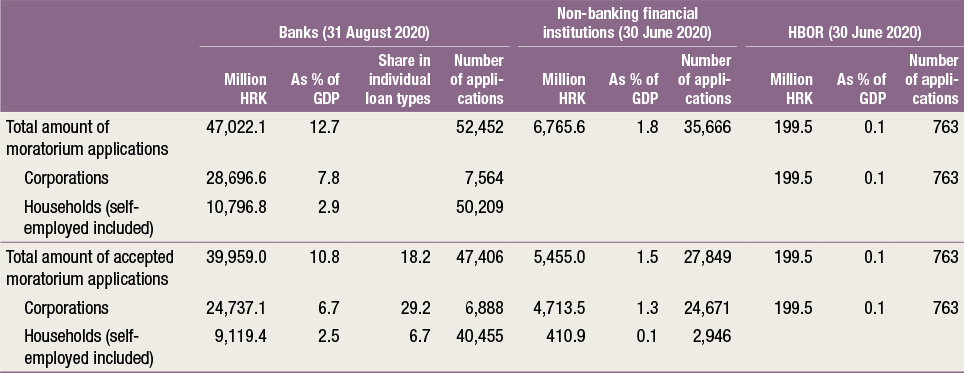

Since numerous citizens and companies were faced with difficulties in relation to their credit obligations, the banks, HBOR and non-banking financial institutions granted them moratoria on these obligations. The amount of moratoria granted totalled HRK 45.6bn, with the banks accounting for the bulk of this amount, having deferred collection of obligations in the amount of almost HRK 40bn.

Table 4 HBOR and HAMAG-BICRO loans, 30 June 2020

Note: Shown as a share of the estimated GDP in 2020 (CNB projection).

Sources: HBOR and HAMAG-BICRO.

Table 5 Moratoria on debtors’ obligations to financial institutions

Note: Shown as a share of the estimated GDP in 2020 (CNB projection).

Sources: CNB, HANFA and HBOR.

Overview of selected measures from ESRB database and supranational mechanisms of economic assistance

As shown by the comprehensive list of measures, numerous member states have focused their efforts and available funds on sectors and activities that by their nature are the most vulnerable to social distancing measures and that have no access to alternative action at the peak of the pandemic. Thus countries of the Mediterranean circle adopted a number of measures focusing on the tourist sector. Greece and Cyprus provide financial support to workers in tourism meeting certain conditions and Spain introduced a 50% exemption from the payment of social contributions for employers in tourism and related sectors. Spain also set up a EUR 10bn fund as temporary capital aid through various instruments for companies that are strategically important in terms of their economic or social impact or criteria of safety, health, infrastructure, communications or contribution to the functioning of financial markets.

Ireland set up assistance programmes worth EUR 200m to facilitate research and development of COVID-19 associated products, promote testing and infrastructure contributing to the development of these products and support the manufacture of products essential for response to the pandemic.

The Czech Republic has instituted an "antivirus C" programme, which implies exemption from social contributions for small employers and subsidises half of the rent paid by entrepreneurs during the period of work suspension due to the emergency situation, provided they meet a number of conditions.

On a supranational level some economic assistance mechanisms have already been launched while others are in a preparatory phase. These include EUR 100bn envisaged under the SURE programme aimed at providing loans to member states to be used to ensure employee income and full employment despite inability to operate or difficulties in operating. The European Investment Bank will ensure EUR 200bn for guarantees for loans to entrepreneurs, with a special emphasis on small and medium-sized entrepreneurs. Also, the European Stability Mechanism will make available EUR 240bn to euro area countries, in amounts equalling up to 2% of GDP of the member states at the end of 2019, which may be used for health care and settlement of the costs associated with the treatment and prevention of the pandemic. A special short-term recovery fund worth EUR 750bn has also been set up to be distributed proportionately in accordance with the degree to which countries have been hit by the pandemic. Since the Republic of Croatia, due to its dependence on tourism and service activities, is among the hardest hit members, the amount that will be made available to it is expected to exceed EUR 10bn.

And finally, the EU increased the flexibility in the use of funds from EU structural funds by enabling member states to transfer funds between various funds and areas to achieve their optimum use in the circumstances of the pandemic.

Glossary

Financial stability is characterised by the smooth and efficient functioning of the entire financial system with regard to the financial resource allocation process, risk assessment and management, payments execution, resilience of the financial system to sudden shocks and its contribution to sustainable long-term economic growth.

Systemic risk is defined as the risk of an event that might, through various channels, disrupt the provision of financial services or result in a surge in their prices, as well as jeopardise the smooth functioning of a larger part of the financial system, thus negatively affecting real economic activity.

Vulnerability, in the context of financial stability, refers to structural characteristics or weaknesses of the domestic economy that may either make it less resilient to possible shocks or intensify the negative consequences of such shocks. This publication analyses risks related to events or developments that, if materialised, may result in the disruption of financial stability. For instance, due to the high ratios of public and external debt to GDP and the consequentially high demand for debt (re) financing, Croatia is very vulnerable to possible changes in financial conditions and is exposed to interest rate and exchange rate change risks.

Macroprudential policy measures imply the use of economic policy instruments that, depending on the specific features of risk and the characteristics of its materialisation, may be standard macroprudential policy measures. In addition, monetary, microprudential, fiscal and other policy measures may also be used for macroprudential purposes, if necessary. Because the evolution of systemic risk and the consequences of such risk, despite certain regularities, may be difficult to predict in all of their manifestations, the successful safeguarding of financial stability requires not only cross-institutional cooperation within the field of their coordination but also the development of additional measures and approaches, when needed.

List of abbreviations

Art. Article

bn billion

b.p. basis points

CB capital conservation buffer

CCB countercyclical capital buffer

CEE Central and Eastern European

CES Croatian Employment Service

CHF Swiss franc

CNB Croatian National Bank

CRD IV Directive 2013/36/EU on access to the activity of credit institutions and the prudential supervision of credit institutions and investment firms

CRR Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms

d.d. dioničko društvo (joint stock company)

DSTI debt-service-to-income ratio

EBA European Banking Authority

EBITDA earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation

ECB European Central Bank

ESRB European Systemic Risk Board

EU European Union

Fed Federal Reserve System

FINA Financial Agency

FOMC Federal Open Market Committee

GDP gross domestic product

G-SII global systemically important institutions buffer

HANFA Croatian Financial Services Supervisory Agency

HRK Croatian kuna

IRB internal ratings-based

LGD loss-given-default

LTD loan-to-deposit ratio

LTI loan-to-income ratio

LTV loan-to-value ratio

NBB National Bank of Belgium

no. number

OG Official Gazette

O-SII other systemically important institutions buffer

O-SIIs other systemically important institutions

Q quarter

SRB systemic risk buffer

Two-letter country codes

AT Austria

BE Belgium

BG Bulgaria

CY Cyprus

CZ Czech Republic

DE Germany

DK Denmark

EE Estonia

ES Spain

FI Finland

FR France

GR Greece

HR Croatia

HU Hungary

IE Ireland

IS Iceland

IT Italy

LV Latvia

LT Lithuania

LU Luxembourg

MT Malta

NL The Netherlands

NO Norway

PL Poland

PT Portugal

RO Romania

SE Sweden

SI Slovenia

SK Slovakia

UK United Kingdom

-

Under Article 395, paragraph (1) of the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR), exposure to a client or group of connected clients may not exceed 25% of a credit institution's eligible capital, with the exception of the transitional period until end-2010 during which this ratio may amount to 50% of eligible capital. The "quick fix" grants discretionary power to competent authorities to reinstitute a transitional period for exposures to central governments and central banks, denominated and financed in the domestic currency of another member state, with their permitted ratio in relation to eligible capital amounting to up to 100% until 31 December 2023, up to 75% in 2024 and up to 50% in 2025. The limits are applied to the values of exposures after accounting for the effect of credit risk mitigation. ↑