In mid-2022, the ECB started the strongest monetary policy tightening cycle since the creation of the euro area. Between July 2022 and June 2023, the key ECB interest rates were increased by a high 400 basis points. The growth in key interest rates triggered an increase in lending and deposit rates at banks in euro area countries, with the pass-through in Croatia being among the weakest. Some of the key factors moderating the intensity of the pass-through in Croatia vis-à-vis other countries that can be singled out are one-off in nature, e.g., the fall in risk premia and the growth of excess liquidity due to the introduction of the euro, while others are of a structural nature, such as a stable and growing deposit base, the role of deposits as the dominant source of bank financing, the relatively low loan-to-deposit ratio, as well as the small share of variable interest rates on loans. The analysis also showed that systemically important banks increased their interest rates on corporate loans, household housing loans and corporate time deposits more strongly than other banks.

There are several mechanisms through which changes in the key ECB interest rates are passed on to bank interest rates.[1] First, the rise in key ECB interest rates affects the funding costs of banks with Eurosystem central banks, on the interbank market and on the bank bond market, which banks pass on to borrowers to a greater or lesser extent to protect margins. Second, a rise in financial market interest rates could encourage companies and citizens to withdraw deposits from banks and invest them in alternative financial instruments such as bonds or money market fund shares, so banks need to raise deposit rates in order not to lose the deposit base, which ultimately also affects their funding costs. Third, in the conditions of large excess liquidity that banks deposit with the Eurosystem central banks and receive interest on them, the interest rate on overnight deposits determines the banks’ opportunity cost of placing funds for some other purpose as well as the minimum return that banks will require when granting some types of loans. Finally, money market interest rates (e.g. EURIBOR), which are affected by the ECB’s monetary policy, are used as reference rates for calculating the interest rate on new loans.

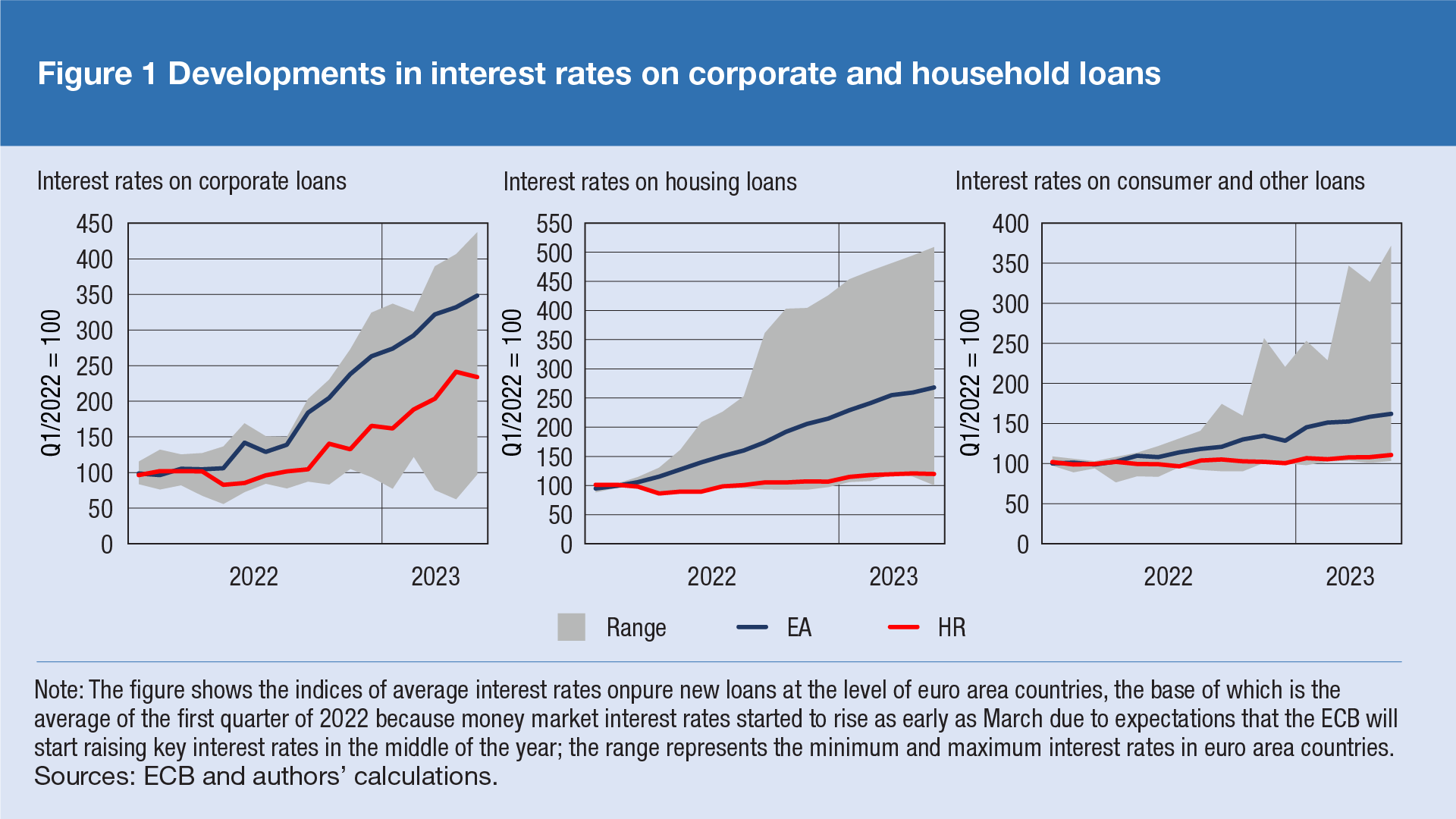

The effects of the ECB’s monetary policy tightening are already visible in Croatia, but the strength of the pass-through of higher policy rates to bank rates is among the weakest in the euro area (Figure 1). For example, from the beginning of 2022 to May 2023, interest rates on corporate loans grew at a much slower pace than the euro area average, while the growth of interest rates on housing, consumer and other loans to households was among the lowest in the euro area (Croatia hovers around the lower bound of the range). Some of the key factors moderating the strength of the pass-through in Croatia vis-à-vis other euro area countries that can be singled out are one-off in nature, e.g., the decline in the country risk premia and the surge in excess liquidity resulting from accession to the euro area,[2] while others are of a structural nature, such as a stable and growing deposit base, the role of deposits as the dominant source of bank financing, the relatively low loan-to-deposit ratio, as well as the small share of variable interest rates on loans.

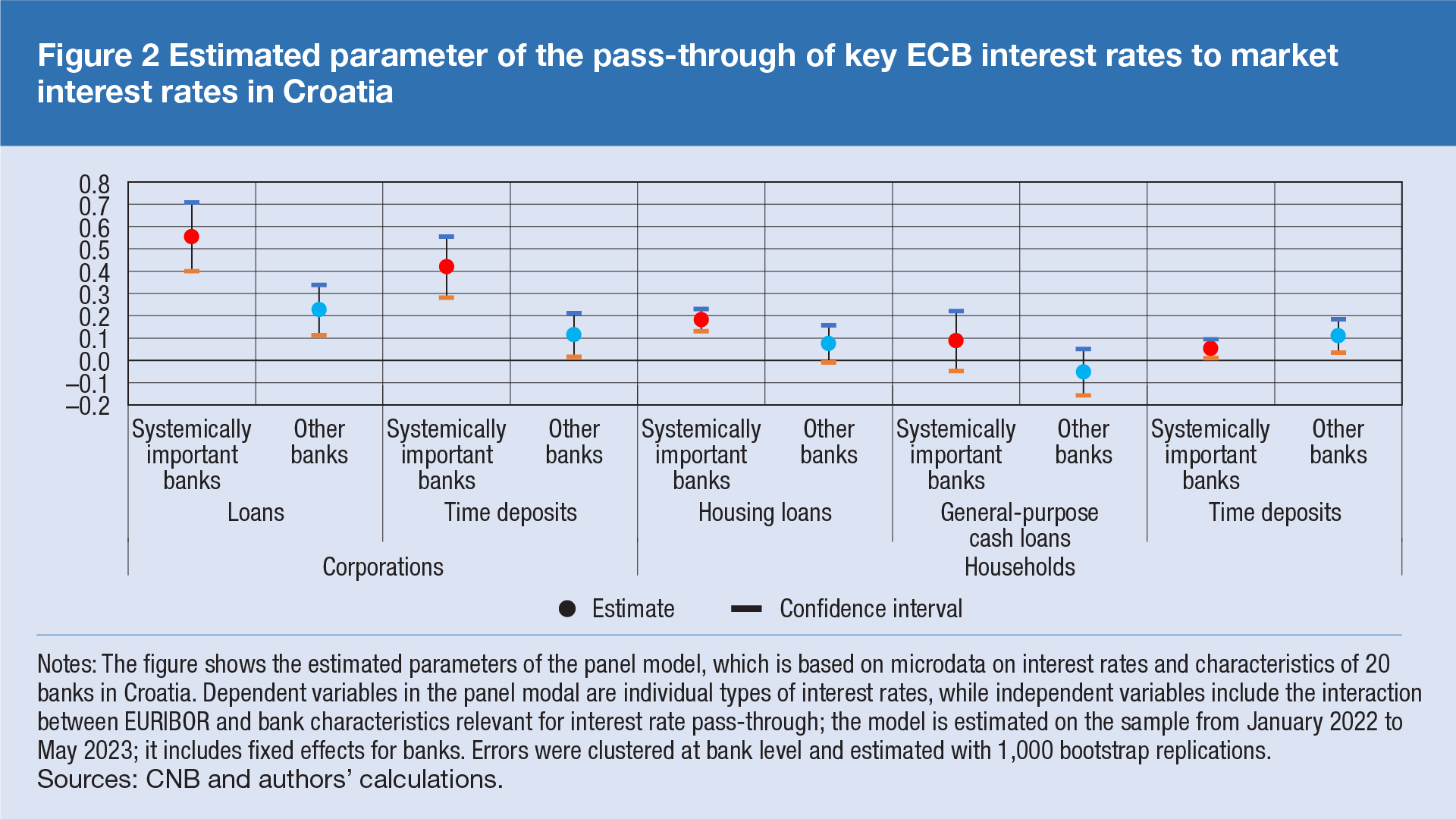

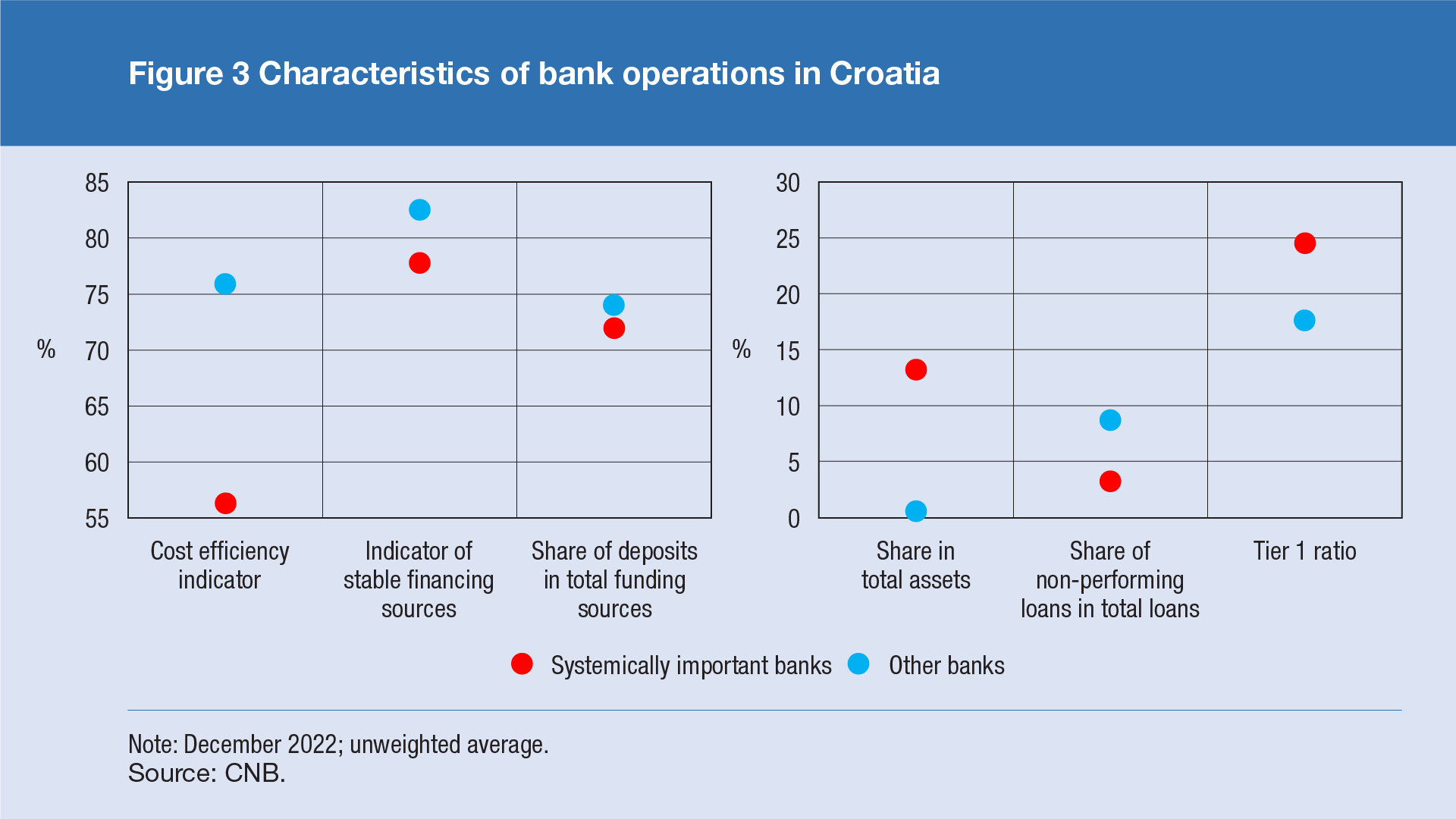

The pass-through of changes in key interest rates also varies across domestic banks. For example, on the increase in EURIBOR of 100 basis points,[3] systemically important banks[4] increased interest rates on corporate loans (around 55 basis points) more strongly than other banks (around 23 basis points), with this effect being slightly more pronounced in long-term loans (Figure 2). There are also differences in the pass-through in case of interest rates on corporate time deposits and interest rates on housing loans to households. This is in line with findings from the literature,[5] where the size of banks is viewed through the prism of market power. Larger banks can use their market position to raise lending rates more and less on deposits in periods of rising key interest rates than smaller banks, while they may lower interest rates at a slower pace in the period when key interest rates fall. Systemically important banks also have a smaller share of non-performing assets, better capitalisation and cost efficiency, and a smaller share of deposits in total funding sources (Figure 3), which contributes to a stronger interest rate pass-through. By contrast, smaller banks build a closer relationship with clients, which may also influence their decisions to set interest rates. On the other hand, there is no significant difference between systemically important and other banks in the pass-through of increases in key interest rates to consumer loans or to household time deposits.

A stronger increase in lending rates than in deposit rates reflects banks’ attempts to maintain interest margin, where banks with a large deposit base have less need to raise deposit rates more strongly in order to attract new depositors.

In addition to cross-banks differentials, interest rate pass-through is also heterogeneous across sectors and instruments. As shown in Figure 2, both bank groups raised interest rates to the corporate sector more strongly than interest rates to households, as well as lending rates compared with deposit rates. A more intensive increase in lending rates than in deposit rates can be explained by banks’ attempts to maintain interest margin. Namely, banks apply higher interest rates only on new loans or loans granted at a variable interest rate, while interest rates on existing loans granted at a fixed interest rate remain unchanged. Therefore, the increase in interest rates has only a partial impact on banks’ loan portfolios and thus on interest income. On the other hand, deposits are usually subject to variable interest rates, so that a higher deposit rate directly affects almost all deposits and thus the costs of bank financing. The difference in the pass-through is also visible across sectors. Interest rates on corporate loans grew more than interest rates on household loans not only because of the statutory interest rate cap which protected households from stronger growth but also due to the subsidy programme offered to households, for example, for housing loans. As regards deposits, corporations have access to alternative sources of financing and, by offering a higher interest rate, banks seek to increase the attractiveness of depositing funds in the form of deposits. On the other hand, households react more slowly to market changes and manage risks with more difficulty, which enables banks to increase interest rates on household deposits more slowly.

The strength of interest rate pass-through is also affected by other characteristics of individual banks, such as their business model, asset quality, efficiency or capital adequacy. Poorer asset quality and a higher share of stable financing sources weaken the pass-through of increases in key interest rates to bank interest rates. Banks with a large share of non-performing claims could additionally attract riskier projects by increasing interest rates, thus increasing the probability of default. This would further increase exposure to credit risk and the probability of additional losses. As a result, profitable banks might be less inclined to change interest rates if the quality of their assets is already low. Furthermore, the strength of interest rate pass-through is weaker in banks that rely more strongly on deposits in their total funding sources. Banks with a high share of deposits, which are less elastic to interest rate changes than other sources of bank financing, may adjust interest rates to market conditions at a slower pace than other banks. In addition, banks with a large deposit base have less need to raise deposit rates more strongly in order to attract new depositors. Also, banks with higher cost efficiency indicators raise their interest rates more slowly, as more efficient banks have greater ability to absorb shocks, which are then only partly transferred to debtors.

To conclude, analysis of the interest rate pass-through is important for monetary policy makers because it determines the efficiency of one of the most important transmission channels of the ECB’s monetary policy – the interest rate channel. The ECB pursues its primary objective of price stability by changing its key interest rates and adapting non-standard monetary policy measures that affect economic activity and prices through various channels, with the interest rate channel being one of the most important.[6] Therefore, it is of utmost importance for monetary policy makers to understand factors that can accelerate or slow down interest rate pass-through and to make it stronger or weaker. However, understanding all relevant factors is challenging at the level of one country and even more challenging at the level of different countries, since in addition to bank characteristics, they may differ in terms of regulations, economic situation, other policies, etc. Large differences in interest rate pass-through may lead to strong heterogeneity in monetary policy transmission across euro area countries, which may make it difficult for the ECB’s Governing Council to set the appropriate monetary policy stance.

-

The relationship between a change in key interest rates of central banks and a change in interest rates of banks is referred to as "interest rate pass-through". ↑

-

The harmonisation of monetary policy instruments led to a reduction in the regulatory costs of bank intermediation as the reserve requirement rate was cut from 9% to 1% and the obligation to maintain the minimum required foreign currency claims was repealed in entirety. This considerably increased free reserves in Croatian banks, which at the beginning of this year reached almost 20% of total banking system assets, one of the highest ratios in the euro area. ↑

-

The empirical literature on interest rate pass-through uses money market interest rates, which reflect changes in key interest rates, as well as market expectations, instead of key interest rates. ↑

-

See the definition and names of systemically important banks in Croatia at https://www.hnb.hr/documents/20182/3689402/h-priopcenje-preispitivanje-sistemski-vaznih-ki-u-RH_29-11-2022.pdf/de064d76-3d16-cdf5-5a02-b1d975c5b69c?t=1669708440373. ↑

-

See, for example, Gregor, J., Melecký, A. and Melecký, M. (2021): Interest rate pass‐through: A meta-analysis of the literature. Journal of Economic Surveys, 35(1), 141-191.; Holton, S. and d’Acri, C. R. (2018): Interest rate pass-through since the euro area crisis, Journal of Banking & Finance, 96, 277-229. ↑

-

For a detailed description of all transmission channels of the ECB’s standard and non-standard monetary policy measures, see Beyer et al. (2017): The transmission channels of monetary, macro-and microprudential policies and their interrelations, ECB Occasional Paper. No. 191. ↑