Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 15

Introductory remarks

The macroprudential diagnostic process consists of assessing any macroeconomic and financial relations and developments that might result in the disruption of financial stability. In the process, individual signals indicating an increased level of risk are detected, according to calibrations using statistical methods, regulatory standards or expert estimates. They are then synthesised in a risk map indicating the level and dynamics of vulnerability, thus facilitating the identification of systemic risk, which includes the definition of its nature (structural or cyclical), location (segment of the system in which it is developing) and source (for instance, identifying whether the risk reflects disruptions on the demand or on the supply side). With regard to such diagnostics, instruments are optimised and the intensity of measures is calibrated in order to address the risks as efficiently as possible, reduce regulatory risk, including that of inaction bias, and minimise potential negative spillovers to other sectors as well as unexpected cross-border effects. What is more, market participants are thus informed of identified vulnerabilities and risks that might materialise and jeopardise financial stability.

Glossary

Financial stability is characterised by the smooth and efficient functioning of the entire financial system with regard to the financial resource allocation process, risk assessment and management, payments execution, resilience of the financial system to sudden shocks and its contribution to sustainable long-term economic growth.

Systemic risk is defined as the risk of events that might, through various channels, disrupt the provision of financial services or result in a surge in their prices, as well as jeopardise the smooth functioning of a larger part of the financial system, thus negatively affecting real economic activity.

Vulnerability, within the context of financial stability, refers to the structural characteristics or weaknesses of the domestic economy that may either make it less resilient to possible shocks or intensify the negative consequences of such shocks. This publication analyses risks related to events or developments that, if materialised, may result in the disruption of financial stability. For instance, due to the high ratios of public and external debt to GDP and the consequentially high demand for debt (re)financing, Croatia is very vulnerable to possible changes in financial conditions and is exposed to interest rate and exchange rate change risks.

Macroprudential policy measures imply the use of economic policy instruments that, depending on the specific features of risk and the characteristics of its materialisation, may be standard macroprudential policy measures. In addition, monetary, microprudential, fiscal and other policy measures may also be used for macroprudential purposes, if necessary. Because the evolution of systemic risk and its consequences, despite certain regularities, may be difficult to predict in all of their manifestations, the successful safeguarding of financial stability requires not only cross-institutional cooperation within the field of their coordination but also the development of additional measures and approaches, when needed.

1. Identification of systemic risks

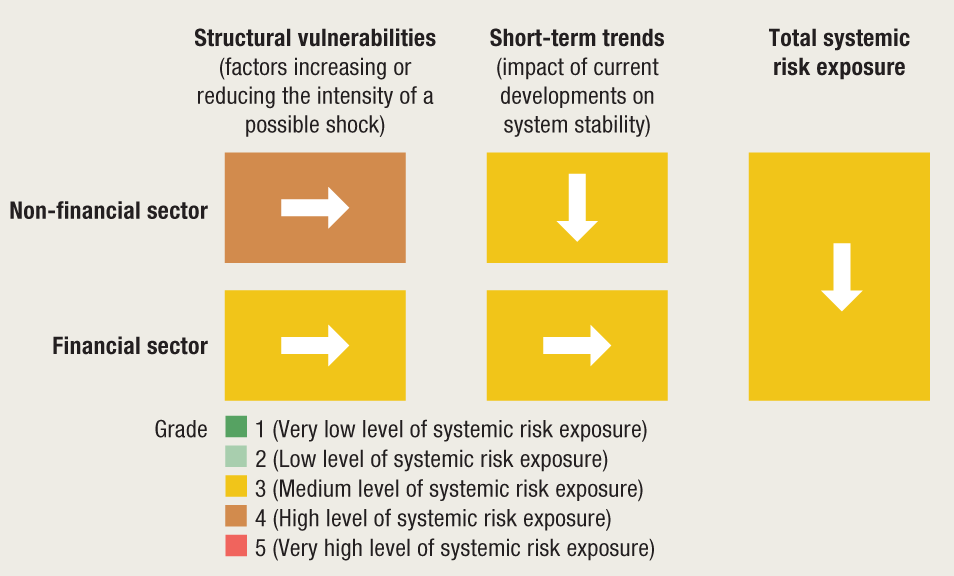

Total systemic risk exposure at the end of the third quarter of 2021 was reduced from high to moderate (Figure 1). The tourist season, which surpassed expectations, and the strengthening of consumer and business optimism were followed by an improved epidemiological situation in the country and the relaxation of measures restricting social gatherings and business, bolstering economic recovery. Such favourable macroeconomic and financial developments alleviated risks associated with short-term economic trends. However, the slowdown in the vaccination rollout and the worsening of the epidemiological situation due to the emergence of the new virus variants and the return of colder weather fuel uncertainty about further recovery. In addition, structural vulnerabilities, which intensify disruptions in the event of the materialisation of unfavourable shocks, remained elevated, reflecting high external and general government debts, an increased unemployment rate and reduced activities compared with the EU average, as well as the relatively high indebtedness of the non-financial corporate sector.

Figure 1 Risk map, third quarter of 2021

Note: The arrows indicate changes from the Risk map in the second quarter of 2021 published in Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 14 (July 2021).

Source: CNB.

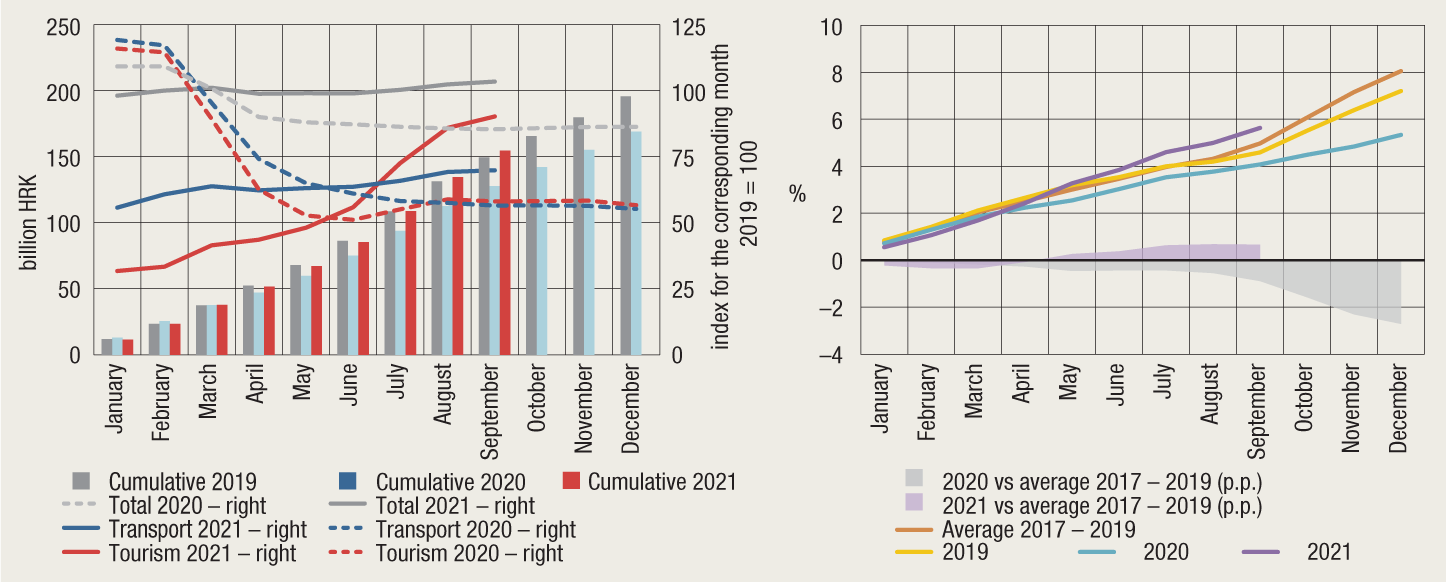

Favourable macroeconomic developments in mid-2021 stem from a good tourist season and the increase in exports of goods and services, among other things. According to the first CBS estimate, in the second quarter economic activity held steady at its beginning-of-year level. The growth of GDP on an annual level stood at an elevated 16.1%, which is primarily due to the base effect, i.e. a strong rebound in economic activity after its sharp fall in the second quarter of 2020. According to volume and financial indicators, the tourist season was better than expected. Tax Administration data indicate that the amounts of fiscalised receipts[1] in tourism (accommodation and food service activities) were about 55% higher in the first nine months of 2021 than in the same period in 2020, but nevertheless remained 10% lower than in the pre-pandemic 2019 (Figure 3, left), while the annual tourist arrival growth rate continued to increase (see release) even though at the beginning of September Croatia was one of the “red” list countries on the map of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. As a result, the intensity of recovery in 2021 as a whole could surpass the CNB’s projections from July this year (Macroeconomic Developments and Outlook No. 10). Growth projections for key trading partners, including those from the euro area, have also recently been revised upwards (see ECB’s Overview). Nevertheless, recovery could still remain unevenly distributed across different economic sectors and countries, largely also depending on the structure of economies, which also has an effect on different fiscal support needs.

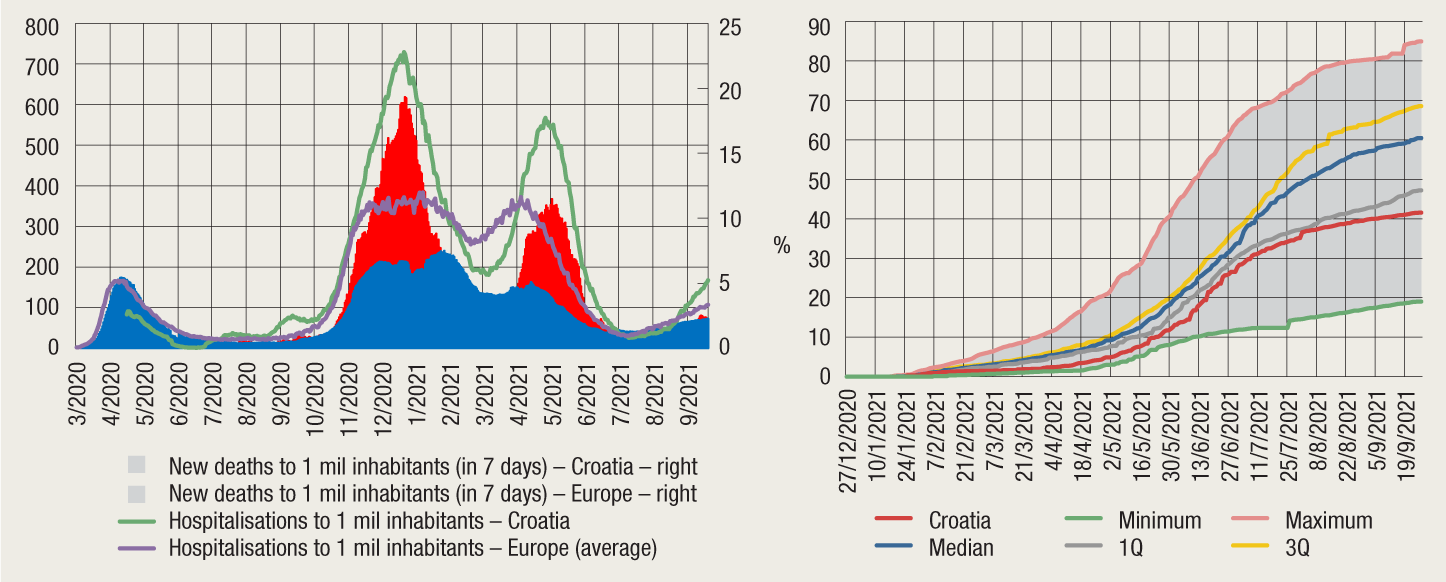

Figure 2 COVID-19 in Croatia and EU: hospitalisations and deaths (left) and population vaccination (right)

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus. Data on deaths and hospitalisations until 19 September 2021, data on population vaccination until 28 September 2021. The grey area on the right panel denotes distribution as a difference between the maximum and the minimum value of vaccination rollout in EU per week, 1Q and 3Q denote the first and the third distribution quartile. Alternative definitions of protection against COVID-19 (e.g. a person having recovered from SARS-CoV-2 or a person having received 1 dose of a two-dose regimen) have been ignored to allow maximum comparability between countries.

Due to a slowdown in the vaccination rollout during the summer and a more aggressive spread of the new virus variants, uncertainty about the final end of the pandemic remains high (Figure 2). Not even the countries with high vaccination rates (such as United Kingdom and Israel) have been able to avoid new waves of the pandemic, albeit of a lesser intensity than previous waves of infection, with a reduced hospital burden. Potential worsening of the epidemiological situation in Croatia and its trading partners could reflect negatively on demand and increase once more the corporate liquidity and solvency risks again that have shrunk in the meantime. This led to almost full abolishment of job preservation grants in September 2021, except for a very limited number of activities that still face disruptions (event industry, travel agencies and similar). Risks related to global supply chain disruptions have been increasing as well. Coupled with a deficit in inputs of raw materials and consumables as well as labour shortages, these risks cause interruptions in the supply of goods and exert upward pressures on prices, in addition to slowing down the rebound of the global economy or parts of it.

Economic recovery has had a favourable impact on the fiscal results in the first six months of 2021. There has been a considerable growth in tax revenues (primarily VAT revenues), which, combined with a somewhat slower increase in expenditures, mostly owing to savings in expenditures on subsidies as a result of a drop in the number of job preservation grant beneficiaries, was reflected positively in the fiscal balance. However, general government debt continued to augment, but its share in GDP edged down to 87.4% at the end of June due to a more pronounced economic recovery. The high level of public debt poses a serious structural risk over the medium term, which, due to considerable government financing by domestic credit institutions (around 22% of their assets is the exposure to the government), is directly reflected in the risk to the stability of the financial system.

There is still abundant liquidity on the international financial markets, with a growing risk of asset overevaluation. Amid high liquidity, low interest rates and a search for higher yields, the stock prices in international markets continue to grow faster than fundamentals, while debt financing conditions remain extremely favourable. However, there is a growing risk that sudden changes in market liquidity could lead to asset repricing.

Financial market trends in Croatia remain stable. There were none of the usual appreciation pressures on the kuna exchange rate during summer months, the ZSE stock exchange index stagnated, with only mild oscillations, and has not yet reached its pre-pandemic level, while money market turnover is still non-existent. Risk premium on government borrowing, measured against CDS, has been on record low levels. Consequently, the financial stress index remained very low. In the course of the pandemic, Croatia kept its current credit rating, with a stable outlook (investment grade rating by Fitch and S&P).

Following the slackening of corporate dynamics during the pandemic, there has still been no significant increase in the number of firms in Croatia closing down. In 2020, the number reduced significantly compared to the usual levels, with an increase in the average age of corporations, while exits from the market only intensified in mid-2021. In the first nine months of 2021, the rate of corporations that discontinued their regular operations has been slightly higher than its average in the period from 2017 to 2019 (Figure 3, right), primarily as a result of voluntary dissolutions. There has been no prominent rise in newly instigated bankruptcy and winding-up cases in the first semester of 2021, mostly due to support measures that still applied at the time, as well as due to the fact that the instigation of bankruptcy proceedings takes at least 60 to 90 days, a period necessary to confirm that a firm is unable to meet its obligations. In addition, even though bankruptcy proceedings are given priority pursuant to the Bankruptcy Act, on average such proceedings last for 3.1 years (according to “Doing business in Croatia”). Pandemic-related risks in the non-financial corporate sector mainly concern activities that are particularly sensitive to social distancing measures. On the other hand, increased use of EU funds has had a favourable impact on the operations of corporations (see results of the analysis here), contributing to the rebound of the economy and improvement of its competitiveness.

Figure 3 Amount of fiscalised receipts (left) and firms discontinuing regular business (right)

Sources: Tax Administration and FINA (processed by the CNB).

Note: The figure shows data on fiscalisation and the share of firms that discontinued regular business in the total number of firms as at end-September.

Following an uptick in the second quarter, there has been a slight worsening of consumer sentiment at the end of summer, even though it still remains relatively high, significantly above the last year’s levels (Consumer Confidence Survey). Consumer optimism is largely evident from a continued increase in demand for housing loans, while there has been only a mild rise in general-purpose cash loans. Although the growth of total loans to households remained moderate (the average rate of change on an annual level stood at 4.6% in August), it accelerated to 10.8% in the housing loan segment by end-August, owing to a new round of the government subsidy programme (see Box 1 for lending standards pertaining to newly-granted housing loans). However, as no second round of subsidies is expected this year, the growth of housing loans could decelerate slightly in the upcoming months. Household debt indicators remained stable, despite a rise in debt. This was due to favourable developments in the labour market, i.e. the return to the employment levels of 2019 and the increase in average wages. Debt servicing burden in the household sector has mildly reduced, under the influence of a continued drop in interest rates.

Residential real estate prices continue to diverge from their long-term trend. After the annual growth rate decelerated to 4.6% in the first quarter of 2021 (from 7.7% in 2020), growth picked up to 6.5% in the second quarter, fuelled by the government subsidy programme. The value of granted loans covered by government the subsidy programme in spring 2021 has hit a record high so far, while decline in interest rates, continued, most pronounced in the months of subsidised housing loans disbursement. The growth of residential real estate prices also stems from low yields and a lack of alternative investments as well as from foreign demand on the Adriatic coast. Thus, prices have been growing more than income and rental costs, decreasing their affordability and return on investments, and have simultaneously been fuelled by an equally strong increase in construction costs. The costs of labour have risen, while a stronger impact of higher prices of materials could materialise with a certain time lag. Real estate market liquidity is growing, and after a temporary decline in 2020, the number of purchase and sale transactions started rising again in the first half of 2021. The exposure of credit institutions in the form of loans secured by real estate is increasing, but is still relatively low compared to own funds, and the banks thus remain resilient to potential disruptions in the real estate market.

Credit institutions remained highly liquid and well-capitalised, while profitability recovered only partially. The banking system total capital ratio held steady above 25%, driven by aversion to riskier investments. Following a sharp fall in 2020, profit increased in the first half of 2021 as a result of a mild rise in non-interest income and reduction in impairment costs. Interest income from lending to all sectors has shrunk. The decline in interest income was most pronounced in the household sector, i.e. in the segment of general-purpose cash loans, that continue to account for the largest share of the total interest income. Banking system profitability is still curbed by low and declining interest rates, i.e. the fall in net interest margin, and thus the increasing spread of digital services could be one of the ways to increase profitability by improving cost-efficiency.

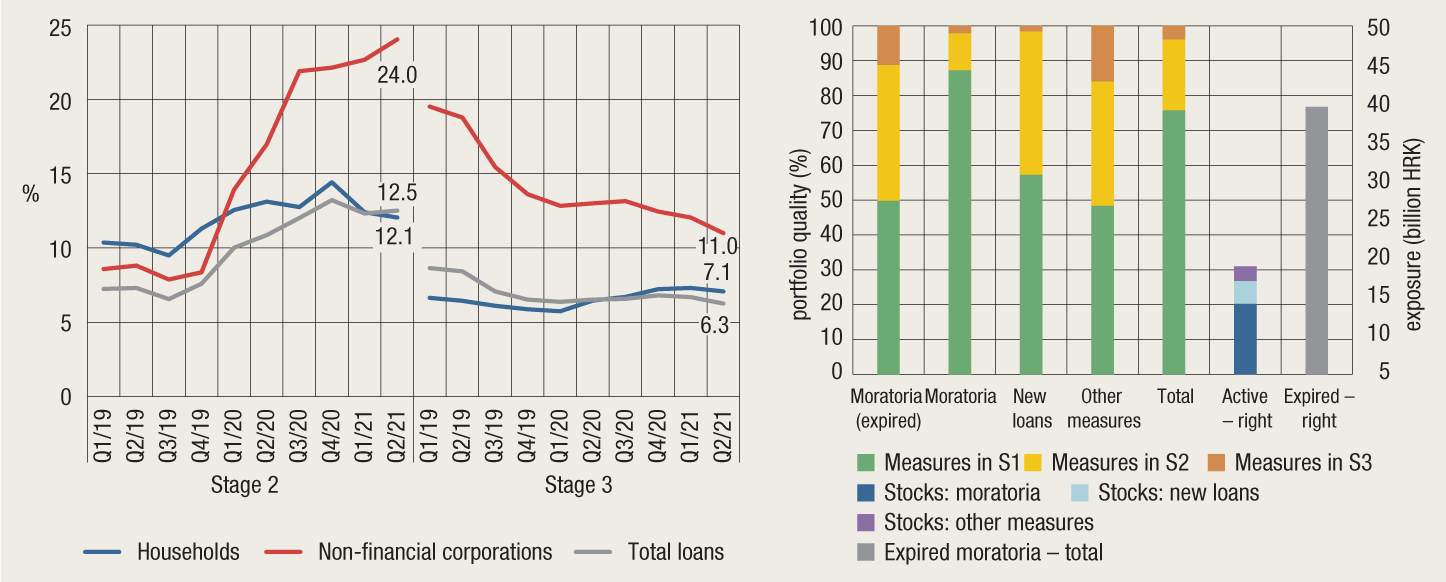

Loan quality remained stable as a result of economic recovery, despite a reduced scope of fiscal support. The share of non-performing loans in total loans continued to decline, mostly in the portfolio of non-financial corporate loans, as a result of the sale of placements, while the impact of the nominal increase in the amount of non-performing loans to their share in the household loans portfolio was alleviated by the growth in loans. In terms of the share of non-performing loans by activities of non-financial corporations, only those of accommodation and food service recorded an increase, which is a result of the strong negative impact of the pandemic on business. Even though the share of support measures to the economy aiming at mitigating the effects of the pandemic has been on the decline (Figure 4, right), only a small portion of exposure to affected clients spilled over to the non-performing loans category (Stage 3) [2], whereas the loans and advance payments classified under Stage 2 marked a significant increase. As the majority of moratoria and fiscal support expired in September, future loan repayment dynamics could be affected by operational difficulties in the event of a significant deterioration of the epidemiological situation, and by more stringent epidemiological measures.

Figure 4 Share of loans in Stage 2 and Stage 3 in total loans and support measures to non-financial corporations hit by the pandemic in the portfolio of credit institutions

Note: Loans in Stage 2 relate to performing loans witnessing a considerable increase in credit risk and loans in Stage 3 relate to those loans witnessing a loss. The figure shows value of gross loans. Credit institutions’ COVID-19 measures directed towards the non-financial corporate sector as at 30 June 2021. S1, S2 and S3 denote loans in Stage 1, Stage 2 and Stage 3, respectively.

Source: CNB.

Box 1 Consumer lending standards on the housing loan market

In late 2020, the CNB started to collect data from credit institutions on consumer lending standards (see Financial Stability No. 22, Box 1.). The collected data provide an insight into the development and distribution of the two most important credit standard indicators in the segment of housing loans: debt service-to-income ratio (hereinafter referred to as: DSTI ratio) and loan-to-value ratio (hereinafter referred to as: LTV ratio). These are preliminary data and may still be revised.

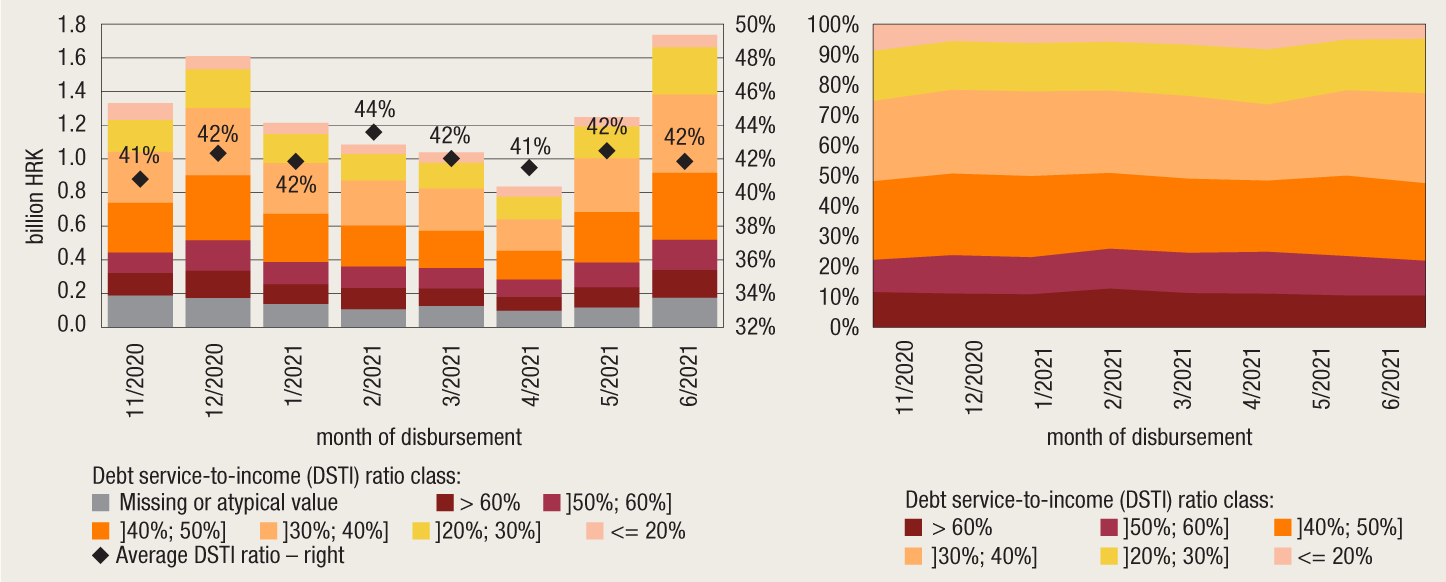

DSTI ratio describes the portion of consumers' (and/or co-debtors') income burdened by debt service payments. It describes the burden of newly-granted housing loans on debtor liquidity. The average weighted debt service-to-income ratio for users of newly-granted housing loans ranges between 41% and 44%, with a very wide distribution of the indicator (Figure 1). If the data on the missing or atypical values of DSTI ratio are disregarded[3], the majority of housing loans disbursed involved loans with DSTI ratio ranging between 30% and 40% (28% of principal) and between 40% and 50% (26% of principal). However, fully 23% of the newly disbursed housing loans have been granted with DSTI ratios exceeding 50%. Loans granted with high DSTI ratios are considered significantly riskier because they make consumers especially vulnerable if there are unfavourable shocks in the macroeconomic environment (such as income shocks or interest rate shocks).

Figure 1 Nominal amounts (left) and shares (right) of principal of disbursed housing loans according to the DSTI ratio classes

Note: The average DSTI ratio over a certain period is weighted by the amount of the disbursed loan principal.

Source: CNB.

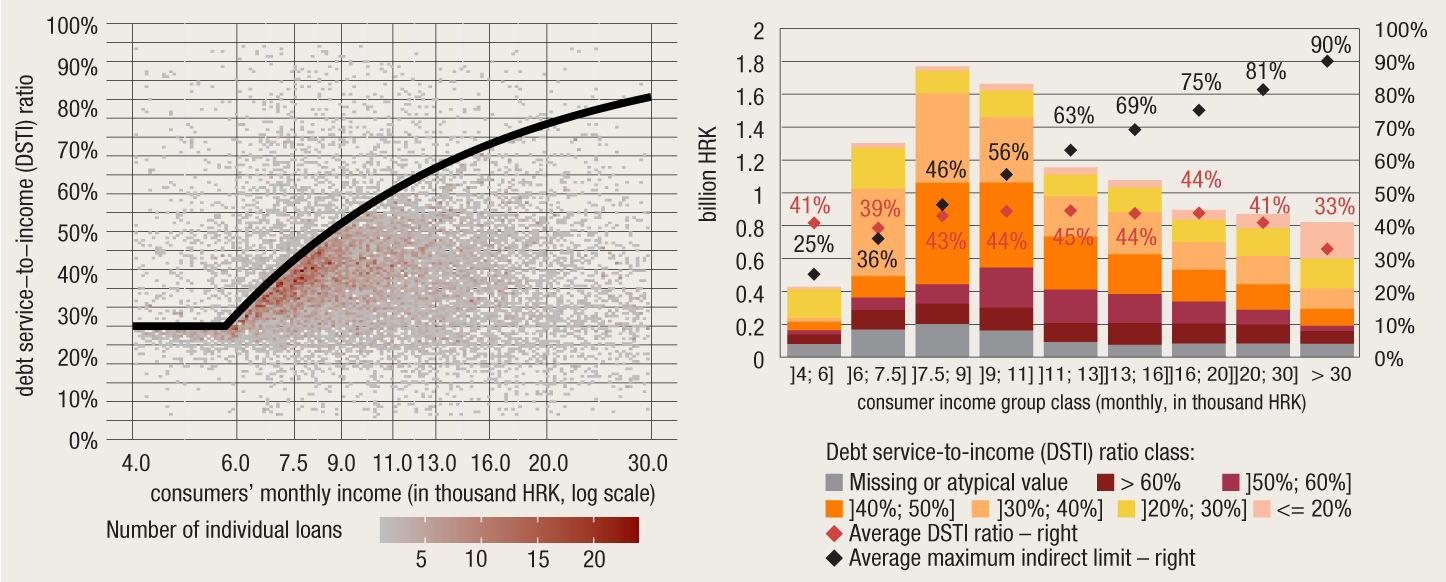

In assessing the risk, DSTI ratio should be considered in combination with a consumer’s income. To be more precise, higher income consumers have more liquidity reserves which they can use in the event of disruptions. Consequently, the indirect limit on DSTI ratio applied to housing loans in the form of the highest amount eligible for seizure depends on consumer income (see: Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 8, Box 1) and is not the same for all consumers on the housing loan market (Figure 2, left). In the case of consumers with a salary below or equal to eight-ninths of the average net salary in the Republic of Croatia[4], the maximum DSTI ratio amounts to 25%, whereas for consumers with an income equal to the average net salary the ratio concerned is 33%, and is even higher for consumers with above-average income – e.g. around 40% for consumers with a monthly income of HRK 7,500, around 50% for those with an income of HRK 9,000, while for those with an income above HRK 11,000, the indirect limit on DSTI ratio stands at 60% and higher[5].

Figure 2 Debt service-to-income ratio (left) and the amount of disbursed principal of housing loans according to the DSTI ratio classes (right) relative to consumer income

Note: The average DSTI ratio is weighted by the amount of the disbursed loan principal. The line on the left panel shows the maximum indirect limit on DSTI ratio depending on consumer income. On the right panel, the average maximum indirect limit in line with the provisions of the Foreclosure Act relates to individual consumer income group classes.

Source: CNB.

The above limits represent the indirect maximum DSTI ratio. However, credit institutions also apply their own criteria based on the analysis of a consumer risk profile. In addition, consumers will not necessarily take out loans with the highest possible ratios, especially those consumers with a higher income who can take on a higher loan servicing burden. Consequently, the average DSTI ratio increases only slightly with income, from about 40% in the case of consumers with incomes below the average, up to a maximum of 45% in the case of consumers with incomes of double the average salary, with a mild decline in the case of even higher income consumers (Figure 2, right). Excluding loans with missing or atypical values of DSTI ratio, almost 49% of the principal of the housing loans disbursed involved loans with DSTI ratios exceeding 40%. Even if it is assumed that the data on DSTI ratios is unreliable in case of individual loans with DSTI ratio higher than the indirect limit laid down in the Foreclosure Act, the share of granted housing loans with a DSTI ratio higher than 40% still accounts for as much as 43% of the principal of total housing loans disbursed in the observed period. It should be noted that around one-third of the observed sample is accounted for by subsidised housing loans under government housing loans subsidy programme, with the government bearing between 30% and 50% of repayment burden in the first five years or more, meaning that the effective DSTI ratio is currently somewhat lower. Overall, there has been a concentration of DSTI ratios of newly-granted housing loans around the implicit limit with a considerable number of consumers experiencing elevated DSTI ratios. On average, housing loans have a repayment period of 21 years, meaning that a considerable portion of consumer income remains burdened by repayment over a relatively long term, in contrast with general-purpose cash loans, for instance, that on average have a repayment period of 7 years.

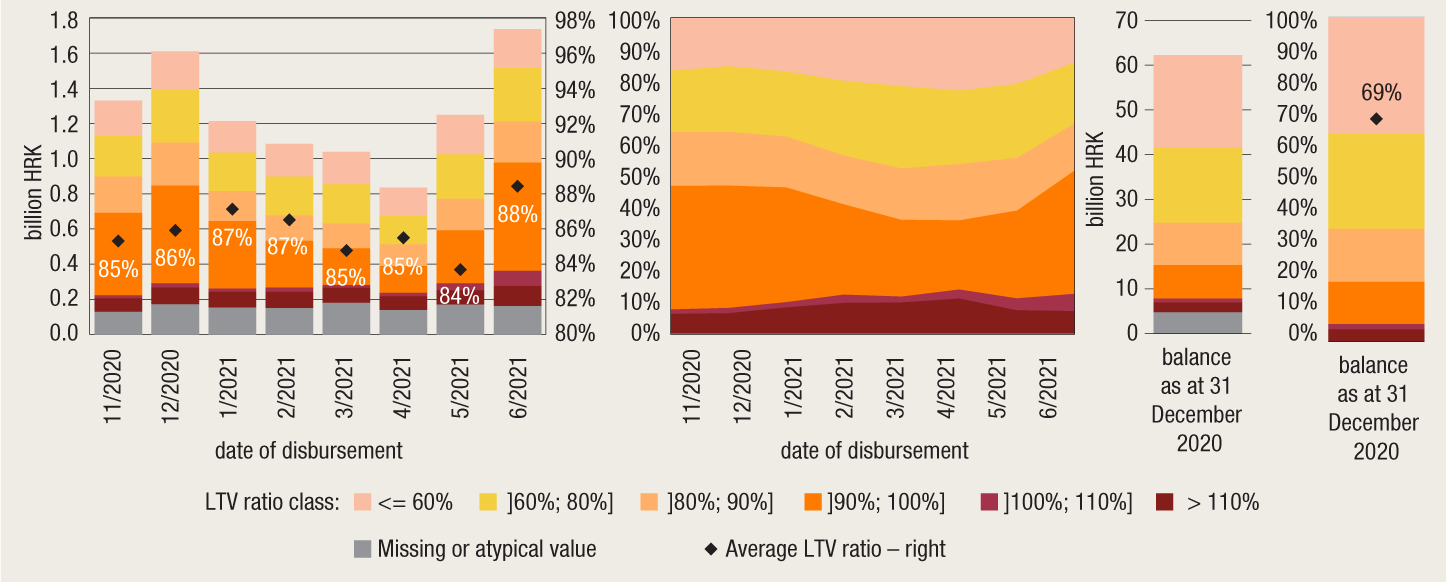

Figure 3 Disbursed amounts of newly-granted loans (left), shares in total disbursed loans (middle) and balances and shares of the principal of housing loans (right) according to the LTV ratio classes

Note: The average LTV ratio is weighted by the amount of the loan principal.

Source: CNB.

In addition to monitoring the debt repayment income burden, it is also important to monitor the indicator related to the coverage of loans by the value of real estate serving as collateral (LTV ratio). To be more precise, LTV ratio serves to ensure the ability of credit institutions to curb potential losses caused by the inability to repay a housing loan. In the observed period, the average LTV ratio of the disbursed housing loans ranges between 84% and 88%. Around 40% of the loan principal disbursed involved loans with LTV ratio below 80% (Figure 3, left). Furthermore, around a third of the disbursed principal involved loans with LTV ratios ranging between 90% and 100% (partly also reflecting subsidised loans under government housing loans subsidy programme, since these loans are more often granted with such ratios), whereas around 10% of principal involved housing loans exceeding the value of real estate used as collateral. However, as the housing loans get repaid, the LTV ratios of the previously granted loans decline with time. Furthermore, since residential real estate prices have gone up in the past years, the distribution of LTV ratio for the stock of all housing loans is considerably more favourable than for newly-granted loans, with an average LTV ratio of 69% (Figure 3, right). Structured by LTV ratio classes, the share of loans with ratios below 80% accounts for around 65% of the total amount of housing loans principal, with the share of loans exceeding the value of real estate (with LTV above 100%) at about 5%.

Although the LTV ratio distribution does not suggest that credit institutions might incur greater losses in the event of an increase in non-performing loans, such a scenario is nevertheless possible in the event of a significant drop in residential real estate prices. Namely, since the value of real estate fluctuates during economic and financial cycles, LTV is a cyclical indicator. In the upward phase residential real estate prices and the amounts of granted loans reinforce each other, while due to expected further price growth, loans are often granted with even higher LTV ratios, which in turn contributes to the further increase in prices and exposure to the real estate market. This is how credit institutions and consumers become vulnerable to possible real estate market disruptions. Overvaluation of real estate may cause the LTV ratios to be downward biased, making the actual amount available to cover the potential loss arising from granted housing loans insufficient[6]. However, given the high capitalisation and the fact that the housing loan portfolio accounts for only one-seventh of Croatian credit institutions’ assets, it is likely that even in the event of an extremely unfavourable real estate market shock (e.g. if there were a price drop of 20%) that increased the share of loans with an LTV ratio above 100%, the risk to the stability of the banking system would be limited.

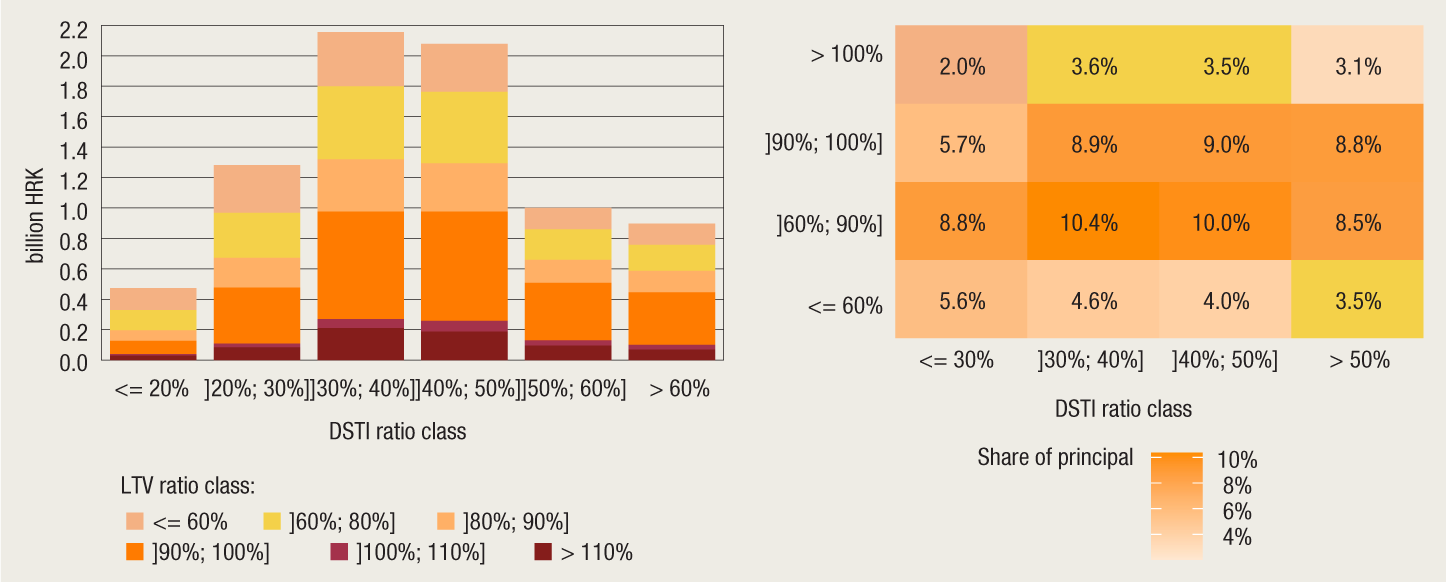

Finally, observation of the joint distribution of loans according to the DSTI and LTV ratio classes (Figure 4) can give a more complete picture of the risk profile of new housing lending. The largest share of principal (around 40%) of housing loans disbursed in the observed period involved loans disbursed with LTV ratio ranging between 60% and 90%, and with DSTI ratio ranging between 30% and 50%, i.e. around the average values of the two ratios. Assuming that the DSTI ratio of 40% and the LTV ratio of 90% can be deemed limits pointing to a relatively higher or smaller risk, the principal of the newly-granted housing loans can be divided into four approximately same-sized groups. Potentially the riskiest group is the one with higher DSTI and LTV ratios, accounting for around 25% of principal. The same goes for the group with higher DSTI ratios, and with LTV ratios below 90%. Furthermore, around 20% of housing loans were granted with a DSTI ratio below 40%, and LTV ratio above 90%, while around 30% of housing loans were granted with the values of both ratios below the assumed “critical” thresholds. This means that even though roughly a half of the principal is disbursed with relatively high DSTI or LTV ratios, the share of principal disbursed with both ratios being elevated accounts for only one-fourth, which makes the housing loan market risk profile somewhat more balanced.

Figure 4 Nominal amounts (left) and shares (right) of principal of housing loans according to LTV and DSTI ratio classes, disbursed from November 2020 to June 2021

Source: CNB.

To conclude, from the data on newly-granted housing loans utilised from November 2020 to June 2021, it is possible to identify segments of the housing loan market that can be deemed risky due to high values of LTV and DSTI ratios. In terms of LTV ratio, seen as the ability to curb losses arising from non-performing loans, the segment of newly-granted housing loans with a ratio above 90% can be considered a source of risk, having in mind that, in the event of a drop in residential real estate prices, the value of collateral could fall below the value of the remaining loan principal. However, as opposed to newly-granted loans, the structure of LTV ratio for the stock of all housing loans is considerably more favourable, with a significantly lower share of loans with a high LTV ratio.

In contrast to the collateral value indicators, the structure of DSTI ratio, seen as the main indicator of the ability of consumers to service their loans regularly, points to somewhat more serious risks present in the housing loan market. To be more precise, according to the data on consumer lending standards, a significant share of the principal of housing loans has been disbursed with high (>40%) and very high (>50%) DSTI ratio, meaning that a larger portion of consumers' (and/or co-debtors') income is burdened with repayment of the loans over a relatively long period. As opposed to LTV ratio, DSTI decreases more slowly over time, only with nominal growth in income, whereas in loans with a variable interest rate, DSTI ratios can even grow if the financing costs of credit institutions increase. Given that debtors remain highly burdened throughout the repayment period, with such burden often decreasing very slowly, debtors whose loans have been granted with a relatively high DSTI ratio remain exposed to potential shocks in the macroeconomic environment. Accordingly, stronger recessions may result in an increased level of non-performing housing loans, which may have an unfavourable impact on the real estate market, causing a feedback-loop on credit institutions’ balance sheets and reinforcing the economic downturn. In order to prevent the mentioned risks from materialising to a systemically more significant extent, it is important to monitor the situation in the real estate and housing loan markets and ensure prudent lending standards on the overall system level.

2. Potential risk materialisation triggers

A slowdown in the vaccination rollout and the spreading of the new strains of the virus could trigger strong new waves of the pandemic. Any tightening of epidemiological measures or reduced consumer mobility and demand for services and products that require personal contact would slow down and postpone economic recovery.

Unfavourable impacts of a weaker corporate dynamics on the performance of corporations create new risk materialisation triggers. The number of voluntary exits of firms from the market increased in the first nine months of 2021, since there is currently no market for them or because they do not see a long-term perspective amid the new circumstances, in the face of a gradual withdrawal of support. On the other hand, although somewhat more prominent in 2021, the number of bankruptcies still remains below the pre-crisis level. Since the number of newly-established firms still continues to be lower than usual, corporate dynamics has remained unfavourable, while the poor business performance of the average firm on the market increases risk to the financial sector.

Sudden changes of operating conditions in the global markets might have an unfavourable impact on Croatia as well. The pandemic has prolonged the accommodative monetary policy stance, while the lingering of extremely low, even negative interest rates contributed to prices of certain types of financial assets hitting record highs, thus increasing repricing risks. Changed expectations of market participants that could swiftly spark an investor run could be a possible trigger for a sudden reversal in the markets. In addition, a faster and stronger turn in the monetary policy of the leading global central banks than what is currently expected, prompted by inflationary pressures remaining steady, would shrink market liquidity and might push investors towards safer forms of investment. The increase in interest rates could also impact risk premiums, which could have a particularly strong effect on countries with pronounced structural macroeconomic unbalances, Croatia included. Global supply chain disruptions, which became more prominent in the early part of 2021 when a number of emerging market economies tightened epidemiological measures, coupled with increased transport costs and intermediate goods prices, could boost inflationary pressures and hinder economic recovery if they become stronger or persist over a long term.

High and growing prices in the residential real estate market, stemming from an increased investor interest amid projected low yields on alternative, make this market more vulnerable to sudden changes in the environment or investor sentiment. Divergence of real estate prices from the income and revenue generated by real estate, accompanied by growing costs on the supply side, increases the possibility of a sudden slump in demand and a fall in market liquidity. Although credit institutions remain highly capitalised, with a relatively small share of exposure covered by real estate compared with other EU countries, the risk of a sudden change in collateral price and marketability could adversely affect their balance sheets and their ability to deal with non-performing claims in the secondary market.

3. Recent macroprudential activities

Favourable macroeconomic developments motivated the Croatian National Bank to repeal the Decision on a temporary restriction of distributions before its planned expiry. In addition, there have been signs of potential emerging accumulation of cyclical systemic risks in the domestic economy, but the countercyclical capital buffer rate remained at 0%, although the Croatian National Bank will promptly react to adjust the rate if needed. Some European Economic Area countries have started tightening their macroprudential policy measures, primarily due to residential real estate market developments and high asset prices, growing household debt and the accumulation of risks related to financing conditions that have remained favourable.

3.1 Repealing the Decision on a temporary restriction of distributions

The Croatian National Bank repealed the Decision on a temporary restriction of distributions, effective as of 1 October 2021, after the analysis in early September showed that since the adoption of the Decision, the circumstances have changed sufficiently to justify such action. Namely, the Decision on a temporary restriction of distributions (OG 4/2021, hereinafter referred to as: Decision) was adopted in January 2021, amid the extreme health-related and economic uncertainties caused by COVID-19 pandemic, building on a similar supervisory measure from March 2020. In order to enhance credit institutions’ resilience and preserve the overall stability of the financial system, the CNB imposed a temporary restriction on credit institutions’ distributions until 31 December 2021. Having regard to the significance and the scope of such a restriction, Article 4 of the Decision lays down that the CNB shall review, until 30 September 2021 at the latest, the existence of the grounds that prompted the adoption of the Decision and that it may, depending on that review, lift the temporary restriction before its expiry.

The analysis conducted by the CNB has shown that credit institutions remained well-capitalised throughout the observed period, owing to reinvested earnings, among other things, and that the stability of their operations has enabled the smooth financing of all domestic sectors. The vaccination rollout and generally a more favourable epidemiological situation ahead of summer 2021 paved the way for a relaxation of epidemiological measures. Combined with a good tourist season, this contributed to economic recovery, especially in the most severely affected activities. In addition, firms’ reliance on fiscal support diminished considerably, while exits of firms from the market remained low. In light of the foregoing, the Croatian National Bank assessed that there was no longer a need to pursue a comprehensive macroprudential measure to restrict distributions, and adopted a decision on its revocation, effective as of 1 October 2021 (OG 106/2021). Even though this has put an end to the general macroprudential restriction on distributions, within the scope of regular supervisory assessment of credit institutions’ risk profile, work will continue on closely monitoring the exposure to risks, especially credit risk, as well as the capital adequacy level and the dividend policy of each institution. In addition, credit institutions are expected to continue applying prudent dividend policies, ensuring their own safety and stability, as well as the long-term sustainability of their operations.

3.2 Continued application of the countercyclical capital buffer rate of zero for the Republic of Croatia in the fourth quarter of 2022

The Croatian National Bank announced that the countercyclical capital buffer rate of 0% will continue to be applied in the fourth quarter of 2022, despite signs of a build-up of cyclical systemic risks. The strong economic recovery that is expected to continue into the second part of the year, along with further favourable financing conditions, supported a moderate increase in the credit activities of banks in the second quarter of 2021. Loans to corporates have remained almost unchanged, while the continued acceleration in household placements mostly mirrors faster growth in housing loans, driven by spring 2021 government housing loans subsidy programme, amid falling interest rates on housing loans. At the same time, residential real estate prices continued to grow, further departing from economic fundamentals. These developments suggest a possible beginning of cyclical systemic risk accumulation in the domestic economy. As the competent macroprudential authority, the CNB will continue to monitor regularly the economic and financial developments and the further evolution of systemic risks, so as to be able to adjust on time the countercyclical capital buffer rate.

3.3 Actions taken at the recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board

In June 2021, the CNB adopted two decisions on non-reciprocity of macroprudential policy measures adopted by Luxembourg and Norway, since the recommended criteria for their reciprocity have not been met. That is, in its Recommendation ESRB/2021/2 of 24 March 2021 and Recommendation ESRB/2021/3 of 30 April 2021, the European Systemic Risk Board recommended the reciprocity of the macroprudential policy measures adopted by the macroprudential authorities of Luxembourg and Norway due to alleviated risks related to the real estate markets in these countries. Since credit institutions in the Republic of Croatia do not have any direct exposures matching the criteria for the application of these measures, exceeding the prescribed materiality thresholds, the CNB, by applying the de minimis principle, did not prescribe the reciprocity of these macroprudential measures. The CNB undertakes, once a year, to review the materiality of exposures referred to above and, should a domestic credit institution meeting the requirements referred to in recommendations ESRB/2021/2 and ESRB/2021/3 fulfil the preconditions prescribed by the stated measure, to review its decision on the reciprocity of the measure.

3.4 Implementation of macroprudential policy in other European Economic Area countries

In light of economic recovery following the crisis caused by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, some European Economic Area countries started tightening their macroprudential policy measures. The central bank of Bulgaria announced raising the countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) rate from the current 0.5% to 1%, to be in effect as of the fourth quarter of 2022. The increase in the CCyB rate was announced due to a swift growth in private sector lending, especially in the household sector, amid economic recovery, continued price increase in the residential real estate market and persisting favourable financing conditions. Having adopted a decision in May 2021 on the CCyB increase from 0.5% to 1% starting as of the third quarter of 2022, the Czech Republic announced a new increase in the CCyB rate to 1.5%, applying from the fourth quarter of 2022, mainly due to a record high number of newly-granted housing loans with dynamic developments on the real estate market, and taking into account high levels of previously accumulated risks in the banks’ balance sheets. The Swedish macroprudential authority also announced that it will be lifting the CCyB rate from 0% to 1% as of the third quarter of 2022, due to continued economic recovery and the existence of elevated risks related to high asset prices, an increase in household debt, but also due to the assumption of risk on the financial markets.

In Denmark, a decision has been made to reactivate the CCyB rate, to be raised from 0% to the 1% it was at before the COVID-19 crisis, with effect from 30 September 2022. Concurrently, the Systemic Risk Council made additional recommendation to the Government to restrict Danish households’ access to interest-only mortgage loans[7] by setting the maximum loan-to-value ratio to 60% for these loans. The primary objective of this recommendation was to build up resilience of borrowers and the overall national economy to shocks that might occur as a result of price change in the real estate market and the rise in interest rates. With the explanation that financial stability and Danish households’ resilience are currently not at risk, the Danish government has chosen not to follow the Council’s recommendation.

Finland and Iceland also tightened their measures aimed at users of housing loans. The Finnish macroprudential authority passed a decision on lowering the current LTV ratio by 5 percentage points, to stand at its pre-pandemic level of 85% for loans secured by residential real estate in the country and for borrowers that are not first-time buyers. LTV ratio will remain at 95% for first-time buyers, which has not changed during the crisis. Iceland has also lowered the LTV ratio for borrowers who are not first-time buyers from 85% to 80%, while it remained unchanged at 90% for first-time buyers.

With the aim of reducing climate-related risks, in accordance with the current national Green Programme, the Hungarian central bank amended its Mortgage Funding Adequacy Ratio Regulation, effective as of July 2021. These amendments, which include, inter alia, a preferential treatment of green mortgage-backed financing, should spur financing of the domestic green economy, as well as the future introduction of green covered bonds.

In June 2021, the French macroprudential authority extended for the second time the national macroprudential policy measure, recommended for reciprocity by the ESRB, for an additional two-year period. This is a macroprudential measure under Article 458 of the Regulation on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms, limiting large exposure of credit institutions to big and highly indebted non-financial corporations with a head office in France to 5% of eligible capital. This national measure first entered into force in July 2018 for a period of two years, and its application was extended in June 2020 for an additional period of one year. By way of its Decision from 2019, the CNB, by applying the de minimis principle, did not prescribe reciprocation of this macroprudential measure.

Table 1 Overview of macroprudential measures applied by EU member states, Iceland and Norway

Note: The listed measures are in line with Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms (CRR) and Directive 2013/36/EU on access to the activity of credit institutions and the prudential supervision of credit institutions and investment firms (CRD IV). The definitions of abbreviations are provided in the List of abbreviations at the end of the publication. Green indicates measures that have been added or changed since the last version of the table. Light red indicates measures that countries have released in response to the crisis triggered by the coronavirus pandemic.

Disclaimer: of which the CNB is aware.

Sources: ESRB, CNB and notifications from central banks and websites of central banks as at 17 September 2021.

For details, see:

https://www.esrb.europa.eu/national_policy/html/index.en.html and https://www.esrb.europa.eu/home/coronavirus/html/index.en.html.

Table 2 Implementation of macroprudential policy and overview of macroprudential measures in Croatia

Note: The definitions of abbreviations are provided in the List of abbreviations at the end of the publication.

Source: CNB.

-

Amount of fiscalised receipts is used as an approximation of income of non-financial corporations. ↑

-

Owing to fiscal support, the contraction in real economic activity has not fully reflected on the banks’ balance sheets, and therefore care must be taken to further monitor future risks, given that the connection between economic and financial losses has weakened in the course of the pandemic. Future calibrations of models used to assess the risk profile of the credit institutions’ clients and the accuracy of the measured quality of portfolios face great challenge, given that they are usually based on historical data. ↑

-

Data quality control is still ongoing, and thus a part of data with very high DSTI ratio values has been excluded from the analysis. ↑

-

Namely, pursuant to the Foreclosure Act (OG 112/2012, 25/2013, 93/2014, 55/2016, 73/2017 and 131/2020), debtors with net salary below the average net salary in the Republic of Croatia have three-quarters of their income exempt from seizure, provided that the exempt part does not exceed two-thirds of the average net salary in the Republic of Croatia. Marginal income is calculated as three-quarters of income equalling two-thirds of the average net salary, and thus amounts to eight-ninths (2/3*4/3) of the average net salary. ↑

-

Progressive growth of the indirect limit on DSTI ratio is due to the fact that for average and above-average incomes, the part of income that cannot be used for repayment is fixed to two-thirds of the average net salary in the Republic of Croatia, which amounted to HRK 4,508.67 in 2020. ↑

-

It should be noted that the manner in which credit institutions value real estate is also crucial for the assessment of collateralisation of housing loan portfolio. In that respect, relatively high LTV ratios do not necessarily reflect insufficient collateral coverage, if a credit institution applies a conservative approach in their valuation. Accordingly, lower LTV ratios do not necessarily presuppose adequate collateral coverage if the valuation of real estate serving as collateral is overly optimistic. In addition to monitoring LTV ratios, microprudential supervision is thus crucial in ensuring proper valuation of collateral. ↑

-

Such loans allow for deferral of principal repayment, meaning that the borrowers only pay interest during the initial agreed period, and once that period ends, they begin paying principal or the principal is fully repaid in a lump sum. ↑